15 KiB

Noise

ノイズ

It's time for a break! We have been playing with all this random functions that looks like TV white noise, our head is still spinning around thinking on shaders, and our eyes are tired. Time to get out for a walk!

We feel the air in our skin, the sun in our face. The world is such a vivid and rich place. Colors, textures, sounds. While we walk we can't avoid noticing the surface of the roads, rocks, trees and clouds.

The stochasticity of this textures could be call "random", but definitely they don't look like the random we were playing before. The “real world” is such a rich and complex place! So, how can we approximate to this level of variety computationally?

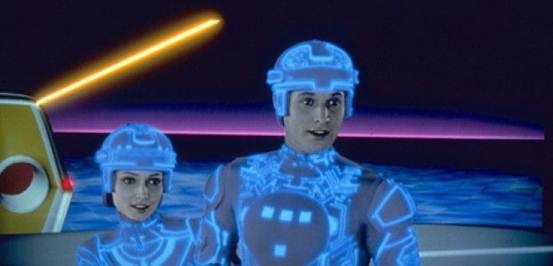

This was the question Ken Perlin was trying to solve arround 1982 when he was commissioned with the job of generating a "more realistic" textures for a new disney movie call "Tron". In response to that he came up with an elegant oscar winner noise algorithm. No biggie.

The following is not the clasic Perlin noise algorithm, but is a good starting point to understand how to generate smooth random aka noise.

In this lines we are doing something similar than the previus chapters, We are subdividing a continus floating value (x````) in integers (i) using [floor()](.../glossary/?search=floor) and obtaining a random (rand()) number for each integer. At the same time we are storing the fractional part of each section using [fract()](.../glossary/?search=fract) and storing it on the f``` variable.

After that you will also see, two commented lines. The first one interpolates each random value linearly.

y = mix(rand(i), rand(i + 1.0), f);

Go ahead and uncomment this line an see how that looks. We use the fract() value store in f to mix() the two random values.

At this point on the book, we learned that we can do better than a linear interpolation. Right?

Now try uncommenting the following line, which use a smoothstep() interpolation instead of a linear one.

y = mix(rand(i), rand(i + 1.0), smoothstep(0.,1.,f));

After uncommenting it, notice how the transition between the peaks got smooth. On some noise implementations you will find that some programers prefere to code their own cubic curves (like the following formula) instead of using the smoothstep().

float u = f * f * (3.0 - 2.0 * f ); // custom cubic curve

y = mix(rand(i), rand(i + 1.0), u); // using it in the interpolation

The smooth random is a game changer for graphical engeneers, it provides the hability to generate images and geometries with an organic feeling. Perlin's Noise Algorithm have been reimplemented over and over in different lenguage and dimensions for all kind of creative uses to make all sort of mesmerizing pieces.

Now is your turn:

-

Make your own

float noise(float x)function. -

Use the noise funtion to animate a shape by moving it, rotating it or scaling it.

-

Make an animated composition of several shapes 'dancing' together using noise.

-

Construct "organic-looking" shapes using the noise function.

-

Once you have your "creature", try to develop further this into a character by assigning it a particular movement.

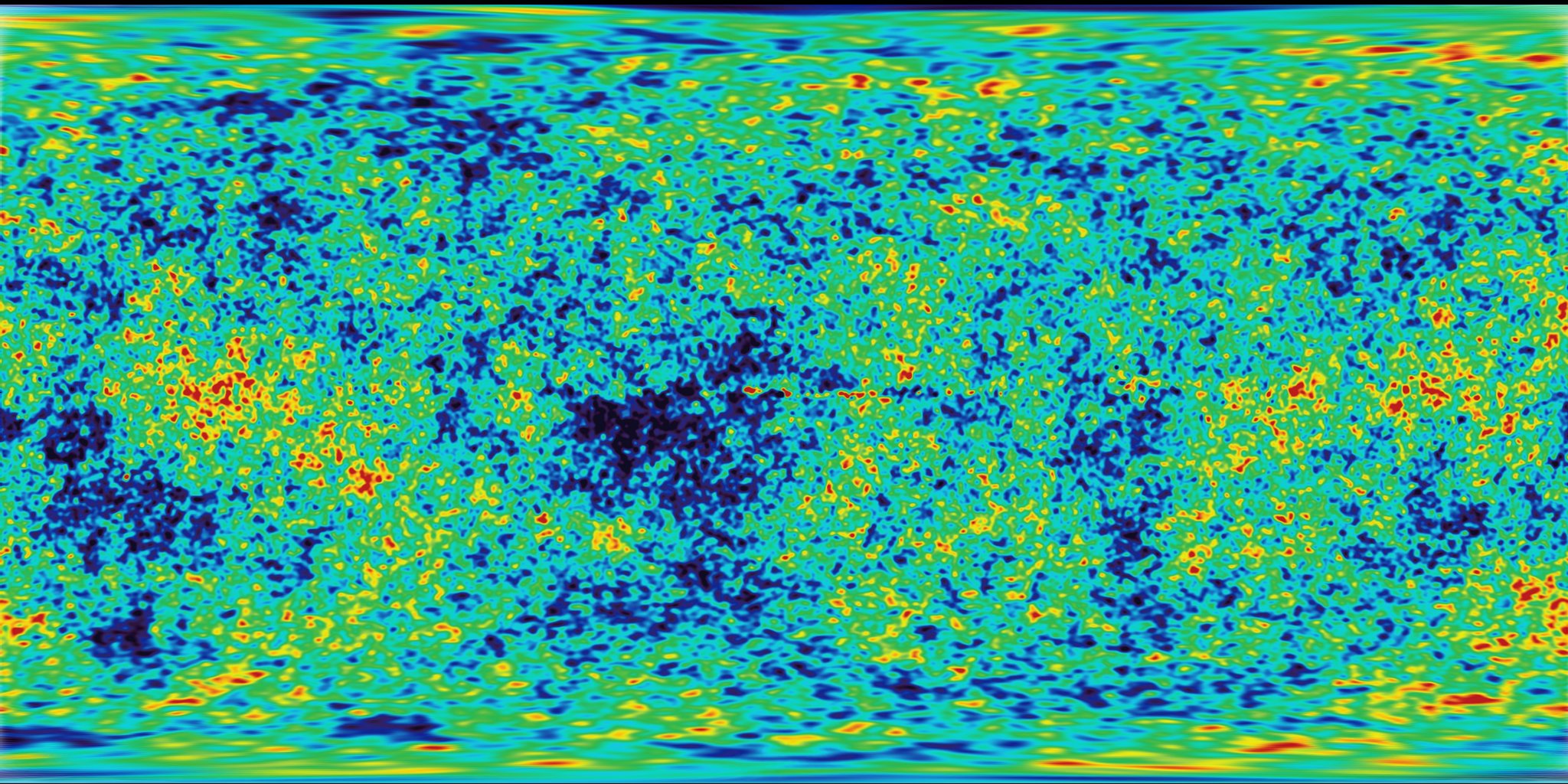

2D Noise

Now that we know how to do noise in 1D, is time to port it to 2D. For that instead of interpolating between two points of a line (fract(x) and fract(x)+1.0) we are going to interpolate between the four coorners of a square area of a plane(fract(st), fract(st)+vec2(1.,0.), fract(st)+vec2(0.,1.) and fract(st)+vec2(1.,1.)).

Similarly if we want to obtain 3D noise we need to interpolate between the eight coorners of a cube. This technique it's all about interpolating values of random. That's why is call value noise.

Similarly to the previus example this interpolation is not liner but cubic, which smoothly interpolates any points inside our squared grid

Take a look to the following noise function.

We start by scaling the space by 5 (line 45) in order. Then inside the noise function we subdived the space in cells similarly that we have done before. We store the integer position of the cell together with fractional inside values. We use the integer position to calculate the four corners corinates and obtain a random value for each one (lines 23-26). Then, finally in line 35 we interpolate 4 random values of the coorners using the fractional value we store before.

Now is your turn, try the following excersices:

-

Change the multiplier of line 45. Try to animate it.

-

At what level of zoom the noise start looking like random again?

-

At what zoom level the noise is imperceptible.

-

Try to hook up this noise function to the mouse coordinates.

-

What if we treat the gradient of the noise as a distance field? Make something interesing with it.

-

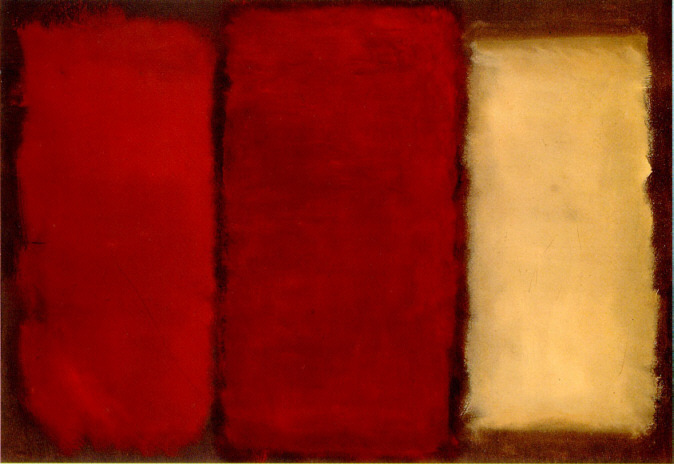

Now that you achieve some control over order and chaos, is time to use that knowledge. Make a composition of rectangles, colors and noise that resemble some of the complexity of the texture of the following painting made by Mark Rothko.

Using Noise on generative designs

As we saw, noise algorithms was original designed to give a natural je ne sais quoi to digital textures. So far all the implementations in 1D and 2D we saw, were interpolation between values reason why is usually call Value Noise, but there are more...

As you discovery on the previus excercises this type of noise tends to look "block", as a solution to this effect in 1985, again, Ken Perlin develop another implementation of the algorithm call Gradient Noise. In it Ken figure out how to interpolate random gradients instead of values. This gradients where the result of 2D noise function that returns directions (represented by a vec2) instead of single values (float). Click in the foolowing image to see the code and how it works.

Take a minute to look to these two examples by Inigo Quilez and pay attention on the differences between value noise and gradient noise.

As a painter that understand how the pigments of their paints works, the more we know about noise implementations the better we will learn how to use it. The following step is to find interesting way of combine and use it.

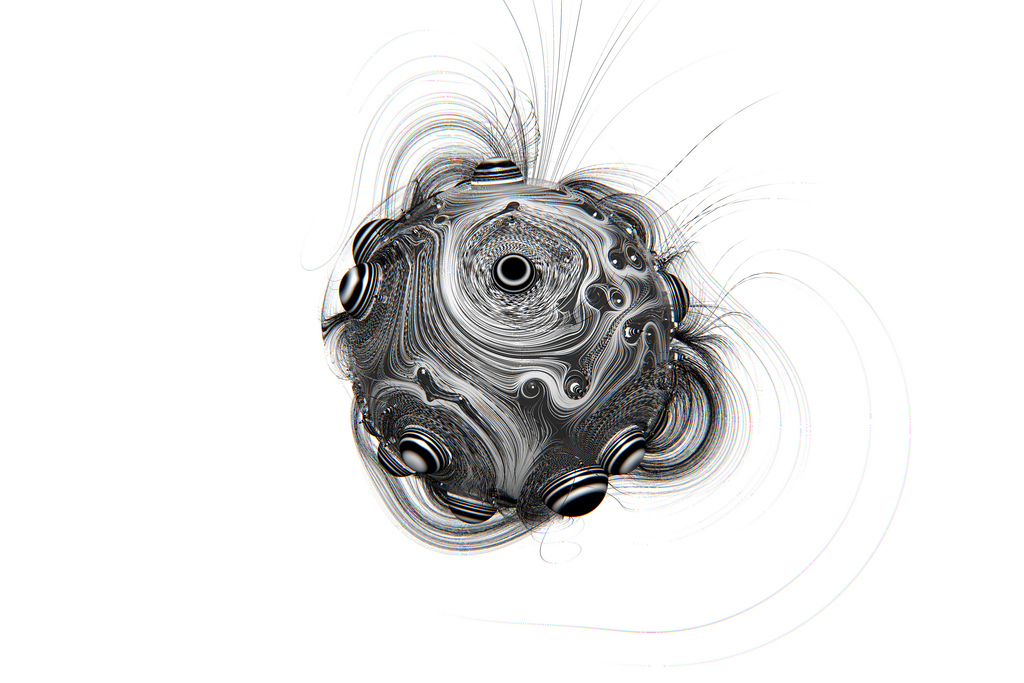

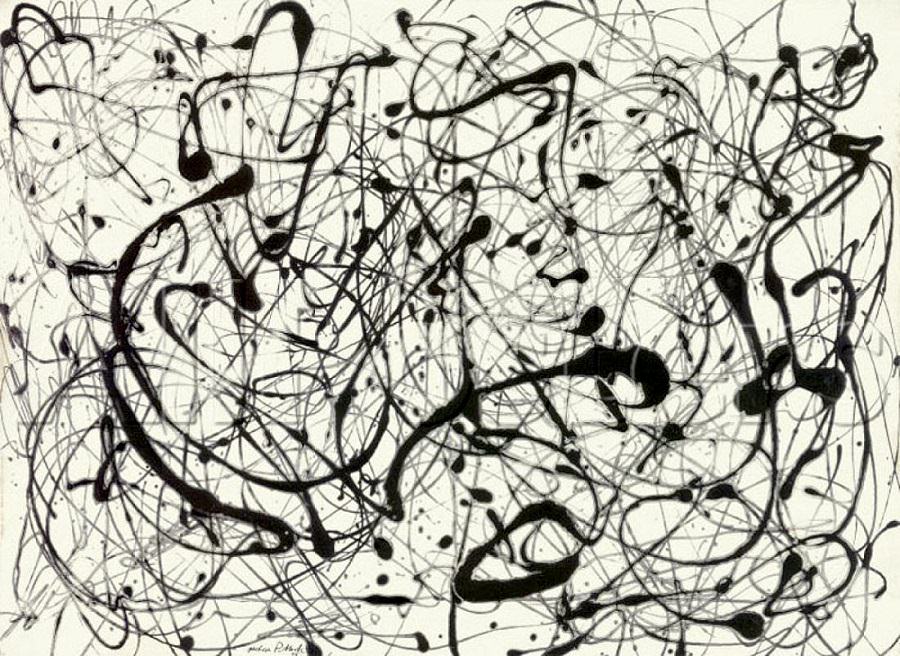

For example, if we use a two dimensional noise implementation to rotate the space where strign lines are render, we can produce the following swirly effect that looks like wood. Again you can click on the image to see how the code looks like

pos = rotate2d( noise(pos) ) * pos; // rotate the space

pattern = lines(pos,.5); // draw lines

Another way to get interesting patterns from noise is to treat it like a distance field and apply some of the tricks described on the Shapes chapter.

color += smoothstep(.15,.2,noise(st*10.)); // Black splatter

color -= smoothstep(.35,.4,noise(st*10.)); // Holes on splatter

A third way of using the noise function is to modulate a shapes, this also requires some of the techniques we learn on the chapter about shapes

For you to practice:

- What other generative pattern can you make? What about granite? marble? magma? water? Find three pictures of textures you are interested and implement them algorithmically using noise.

- Use noise to modulate a shapes.

- What about using noise for motion? Go back to the Matrix chapter and use the translation example that move a the "+" around to apply some random and noise movements to it.

- Make a generative Jackson Pollock

Simplex Noise

For Ken Perlin the success of his algorithm wasn't enough. He thought it could performance better. In Siggraph 2001 he presented the "simplex noise" in wich he achive the following improvements over the previus one:

- An algorithm with lower computational complexity and fewer multiplications.

- A noise that scales to higher dimensions with less computational cost.

- A noise without directional artifacts

- A noise with well-defined and continuous gradients that can be computed quite cheaply

- An algorithm that is easy to implemnt in hardware

Yeah, right? I know what you are thinking... "Who is this man?". Yes, his work is fantastic! But seriusly, How he did that? Well we saw how for two dimensions he was interpolating 4 points (coorners of a square); also we can correctly preasume that for three (see an implementation here) and four dimensions we need to interpolate 8 and 16 points. Right? In other words for N dimensions you need to smoothly interpolate 2 to the N points (2^N). But Ken smartly notice that although the obvious choice for a space-filling shape is a squar, the actually simpliest shape in 2D is the equilateral triangle. So he start by replace the squared grid (we finnaly learn how to use) for a simplex grid of equilateral triangles.

The simplex shape for N dimensions is a shape with N + 1 corners. In other words one less corner to compute in 2D, 4 less coorners in 3D and 11 less coorners in 4D! That's a huge improvement!

So then, in two dimension the interpolation happens, similarly than regular noise, by interpolating the values of the corners of a section. But, in this particular case, because we are using a simplex grid, we just need to interpolate the sum of only 3 coornes ( contributors).

How the simplex grid works? In another brillant and elegant move, the simplex grid can be obtain by subdividing the cells of a regular 4 corners grid into two isoceles triangles and then skewing it unitl each triangle is equilateral.

Then, as Stefan Gustavson describe in this paper: "...by looking at the integer parts of the transformed coordinates (x,y) for the point we want to evaluate, we can quickly determine which cell of two simplices that contain the point. By also compareing the magnitudes of x and y, we can determine whether the points is in the upper or the lower simplex, and traverse the correct three corners points.".

On the following code you can uncomment the line 44 to see how the grid is skew and then line 47 to see how a simplex grid can be constructed. Note how on line 22 we are subdiving the skewed squared on two equilateral triangles just buy detecting if x > y ("lower" triangle) or y > x ("upper" triangle).

Other improvements introduce by Perlin in the Simplex Noise, is the replacement of the Cubic Hermite Curve ( f(x) = 3x^2-2x^3 , wich is identical to the (.../glossary/?search=smoothstep) function ) for a Quintic Hermite Curve ( f(x) = 6x^5-15x^4+10x^3 ). This makes both ends of the curve more "flat" and by gracefully stiching with the next one. On other words you get more continuos transition between the cells. You can watch this by uncommenting the second formula on the following graph example (or by see the two equations side by side here).

Note how the ends of the curve changes. You can read more about this in on words of Ken it self in this paper.

All this improvements result on a master peach of algorithms known as Simplex Noise. The following is an GLSL implementation of this algorithm made by Ian McEwan (and presented in this paper) which is probably over complicated for educational porposes because have been higly optimized, but you will be happy to click on it and see that is less cryptic than you expect.

Well enought technicalities, is time for you to use this resource in your own expressive way:

-

Contemplate how each noise implementation looks. Imagine them as a raw material. Like a marble rock for a sculptor. What you can say about about the "feeling" that each one have? Squinch your eyes to trigger your imagination, like when you want to find shapes on a cloud, What do you see? what reminds you off? How do you imagine each noise implementation could be model into? Following your guts try to make it happen on code.

-

Make a shader that project the ilusion of flow. Like a lava lamp, ink drops, watter, etc.

- Use Signed Noise to add some texture to a work you already made.

In this chapter we have introduce some control over the chaos. Is not an easy job! Becoming a noise-bender-master takes time and efford.

On the following chapters we will see some "well-know" techniques to perfect your skills and get more out of your noise to design quality generative content with shaders. Until then enjoy some time outside contemplating nature and their intricate patterns. Your hability to observe need's equal (or probably more) dedication than your making skills. Go outside and enjoy the rest of day!

"Talk to the tree, make friends with it." Bob Ross