12 KiB

Architecture Overview

Unidirectional data flow

Firefox for Android's presentation layer architecture is based on the concept of "unidirectional data flow." This is a popular approach in client side development, especially on the web, and is core to Redux, MVI, Elm Architecture, and Flux. Our architecture is not identical to any of these (and they are not identical to each other), but the base concepts are the same. For a basic understanding of the motivations and approach, see the official Redux docs. For an article on when unidirectional data flow is and is not a good approach, see this. These are both written from the perspective of React.js developers, but the concepts are largely the same.

Our largest deviation from these architectures is that while they each recommend one large, global store of data, we have a single store per screen and several other global stores. This carries both benefits and drawbacks, which will be covered later in this document.

Important types

Store

Overview

A store of State.

See mozilla.components.lib.state.Store

Holds app State.

Receives Actions, which are used to compute new State using Reducers and can have Middlewares attached which respond to and manipulate actions.

Description

Maintains a State, a Reducer to compute new State, and Middleware. Whenever the Store receives a new Action via store.dispatch(action), it will first pass the action through its chain of Middleware. These middleware can initiate side-effects in response, or even consume or change the action. Finally, the Store computes new State using previous State and the new action in the Reducer. The result is then stored as the new State, and published to all consumers of the store.

It is recommended that consumers rely as much as possible on observing State updates from the store instead of reading State directly. This ensures that the most up to date State is always used. This can prevent subtle bugs around call order, as all observers are notified of the same State change before a new change is applied.

There are several global stores like AppStore and BrowserStore, as well as Stores scoped to individual screens. Screen-based Stores can be persisted across configuration changes, but are generally created and destroyed during fragment transactions. This means that data that must be shared across Stores should be lifted to a global Store or should be passed as arguments to the new fragment.

Screen-based Stores should be created using StoreProvider.get.

State

Overview

Description of the state of a screen or other area of the app.

See mozilla.components.lib.state.State

Description

Simple, immutable data object that contains all of the backing data required to display a screen. This should ideally only include Kotlin/Java data types which can be easily tested, avoiding Android platform types. This is especially true of large, expensive types like Context or View which should never be included in State.

As much as possible, the State object should be an accurate, 1:1 representation of what is actually shown on the screen. That is to say, the screen should look exactly the same any time a State with the same values is emitted, regardless of any previous changes. This is not always possible as Android UI elements are very stateful, but it is a good goal to aim for.

One major benefit of rendering a screen based on a State object is its impact on testing. UI tests are notoriously difficult to build and maintain. If we are able to build a simple, reproducible View (i.e., if we can trust that the View will render as expected), that allows us to test our UI by verifying the correctness of our State object.

This also gives us a major advantage when debugging. If the UI looks wrong, check the State object. If it's correct, the problem is in the View. If not, check that the correct Action was sent. If so, the problem is in the reducer. If not, check the component that sent the Action. This helps us quickly narrow down problems.

Action

Overview

Simple description of a State change or a user interaction. Dispatched to Stores.

See mozilla.components.lib.state.Action

Description

Simple data object that carries information about a State change to a Store. An Action describes something that happened, and carries any data relevant to that change. For example, HistoryFragmentAction.ChangeEmptyState(isEmpty = true), captures that the State of the history fragment has become empty.

Reducer

Overview

Pure function used to create new State objects.

See mozilla.components.lib.state.Reducer

Referenced by: Store

Description

A function that accepts the previous State and an Action, then combines them in order to return the new State. It is important that all Reducers remain pure. This allows us to test Reducers based only on their inputs, without requiring that we take into account the state of the rest of the app.

Note that the Reducer is always called serially, as state could be lost if it were ever executed in parallel.

Middleware

Overview

A Middleware sits between the store and the reducer. It provides an extension point between dispatching an action, and the moment it reaches the reducer.

Description

A Middleware responds to actions by performing side-effects, and can also be used to rewrite an Action, intercept an Action, or dispatch additional Actions.

The Store will create a chain of Middleware instances and invoke them in order. Every Middleware can decide to continue the chain or disrupt the chain. A Middleware has no knowledge of what comes before or after it in the chain.

View

Overview

Initializes UI elements, then updates them in response to State changes

Observes: Store

Description

The view defines the mapping of State to UI. This can include XML bindings, Composables, or anything in between.

Views should be as dumb as possible, and should include little or no conditional logic outside of determining which branch of a view tree to display based on State. Ideally, each primitive value in a State object is set on some field of a UI element.

Views set listeners to UI elements, which trigger dispatches of Actions to Stores.

In some cases, it can be appropriate to initiate side-effects from the view when observing State updates from the Store. For example, a menu might be displayed.

Important notes

- Unlike other common implementations of unidirectional data flow, which typically have one global Store of data, we maintain smaller Stores for each screen and several global Stores.

- There is often no need to maintain UI state for views that are destroyed, and this allows us to to operate within the physical hardware constraints presented by Android development, such as having more limited memory resources.

- Stores that are local to a feature or screen should usually be persisted across configuration changes in a ViewModel by using StoreProvider.get.

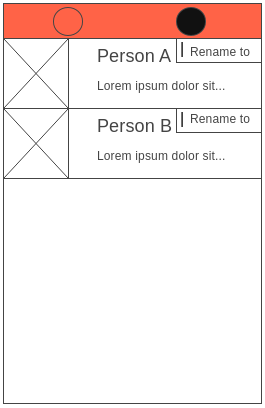

Simplified Example

When reading through live code trying to understand an architecture, it can be difficult to find canonical examples, and often hard to locate the most important aspects. This is a simplified example using a hypothetical app that should help clarify the above patterns.

This app currently has three (wonderful) features.

- Clicking on one of the colored circles will update the toolbar color

- Clicking on 'Rename', typing a new name, and selecting return will update the name of the contact

- Clicking anywhere else on a contact will navigate to a text message fragment

These link to the architectural code that accomplishes those features:

Historical architecture components

There are some out-of-date architecture components that may still be seen throughout the app. The original documentation for these components is captured below in order to preserve context, but should be removed once these components are refactored out.

For more context on when and why these components were removed, see the RFC proposing their removal.

Known Limitations (of historical components, copied from above)

- Many Interactors have only one dependency, on a single Controller. In these cases, they typically just forward each method call on and serve as a largely unnecessary layer. They do, however, 1) maintain consistency with the rest of the architecture, and 2) make it easier to add new Controllers in the future.

Interactor

Overview

Called in response to a direct user action. Delegates to something else

Calls: Controllers, other Interactors

Description

This is the first object called whenever the user performs an action. Typically this will result in code in the View that looks something like some_button.onClickListener { interactor.onSomeButtonClicked() } . It is the Interactors job to delegate this button click to whichever object should handle it.

Interactors may hold references to multiple other Interactors and Controllers, in which case they delegate specific methods to their appropriate handlers. This helps prevent bloated Controllers that both perform logic and delegate to other objects.

Sometimes an Interactor will only reference a single Controller. In these cases, the Interactor will simply forward calls to equivalent calls on the Controller. The Interactor does very little in these cases, and exists only to be consistent with the rest of the app.

Note that prior to the introduction of Controllers, Interactors handled the responsibilities of both objects. You may still find this pattern in some parts of the codebase, but it is being actively refactored out.

Controller

Overview

Determines how the app should be updated whenever something happens

Calls: Store, library code (e.g., forward a back-press to Android, trigger an FxA login, navigate to a new Fragment, use an Android Components UseCase, etc)

Description

This is where much of the business logic of the app lives. Whenever called by an Interactor, a Controller will do one of the three following things:

- Create a new Action that describes the necessary change, and send it to the Store

- Navigate to a new fragment via the NavController. Optionally include any state necessary to create this new fragment

- Interact with some third party manager. Typically these will update their own internal state and then emit changes to an observer, which will be used to update our Store

Controllers can become very complex, and should be unit tested thoroughly whenever their methods do more than delegate simple calls to other objects.