| .. | ||

| .vscode | ||

| src | ||

| Cargo.lock | ||

| Cargo.toml | ||

| kernel | ||

| kernel8.img | ||

| Makefile | ||

| README.md | ||

Tutorial 11 - Virtual Memory

tl;dr

The MMU is turned on; A simple scheme is used: static 64 KiB page tables; For educational

purposes, we write to a remapped UART.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- MMU and paging theory

- Approach

- Address translation examples

- Zero-cost abstraction

- Test it

- Diff to previous

Introduction

Virtual memory is an immensely complex, but important and powerful topic. In this tutorial, we start

slow and easy by switching on the MMU, using static page tables and mapping everything at once.

MMU and paging theory

At this point, we will not re-invent the wheel and go into detailed descriptions of how paging in modern application-grade processors works. The internet is full of great resources regarding this topic, and we encourage you to read some of it to get a high-level understanding of the topic.

To follow the rest of this AArch64 specific tutorial, I strongly recommend that you stop right

here and first read Chapter 12 of the ARM Cortex-A Series Programmer's Guide for ARMv8-A before

you continue. This will set you up with all the AArch64-specific knowledge needed to follow along.

Back from reading Chapter 12 already? Good job 👍!

Approach

- The generic

kernelpart:src/memory/mmu.rsprovides architecture-agnostic descriptor types for composing a high-level data structure that describes the kernel's virtual memory layout:memory::mmu::KernelVirtualLayout. - The

BSPpart:src/bsp/raspberrypi/memory/mmu.rscontains a static instance ofKernelVirtualLayoutand makes it accessible throug the functionbsp::memory::mmu::virt_mem_layout(). - The

aarch64part:src/_arch/aarch64/memory/mmu.rscontains the actualMMUdriver. It picks up theBSP's high-levelKernelVirtualLayoutand maps it using a64 KiBgranule.

Generic Kernel code: memory/mmu.rs

The descriptor types provided in this file are building blocks which help to describe attributes of different memory regions. For example, R/W, no-execute, cached/uncached, and so on.

The descriptors are agnostic of the hardware MMU's actual descriptors. Different BSPs can use

these types to produce a high-level description of the kernel's virtual memory layout. The actual

MMU driver for the real HW will consume these types as an input.

This way, we achieve a clean abstraction between BSP and _arch code, which allows exchanging one

without needing to adapt the other.

BSP: bsp/raspberrypi/memory/mmu.rs

This file contains an instance of KernelVirtualLayout, which stores the descriptors mentioned

previously. The BSP is the correct place to do this, because it has knowledge of the target

board's memory map.

The policy is to only describe regions that are not ordinary, normal chacheable DRAM. However, nothing prevents you from defining those too if you wish to. Here is an example for the device MMIO region:

RangeDescriptor {

name: "Device MMIO",

virtual_range: || {

RangeInclusive::new(memory::map::mmio::BASE, memory::map::mmio::END_INCLUSIVE)

},

translation: Translation::Identity,

attribute_fields: AttributeFields {

mem_attributes: MemAttributes::Device,

acc_perms: AccessPermissions::ReadWrite,

execute_never: true,

},

},

KernelVirtualLayout itself implements the following method:

pub fn get_virt_addr_properties(

&self,

virt_addr: usize,

) -> Result<(usize, AttributeFields), &'static str>

It will be used by the _arch/aarch64's MMU code to request attributes for a virtual address and

the translation of the address. The function scans for a descriptor that contains the queried

address, and returns the respective findings for the first entry that is a hit. If no entry is

found, it returns default attributes for normal chacheable DRAM and the input address, hence telling

the MMU code that the requested address should be identity mapped.

Due to this default return, it is technicall not needed to define normal cacheable DRAM regions.

AArch64: _arch/aarch64/memory/mmu.rs

This file contains the AArch64 MMU driver. The paging granule is hardcoded here (64 KiB page

descriptors).

The actual page tables are stored in a global instance of the PageTables struct:

/// A table descriptor for 64 KiB aperture.

///

/// The output points to the next table.

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

#[repr(transparent)]

struct TableDescriptor(u64);

/// A page descriptor with 64 KiB aperture.

///

/// The output points to physical memory.

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

#[repr(transparent)]

struct PageDescriptor(u64);

/// Big monolithic struct for storing the page tables. Individual levels must be 64 KiB aligned,

/// hence the "reverse" order of appearance.

#[repr(C)]

#[repr(align(65536))]

struct PageTables<const N: usize> {

/// Page descriptors, covering 64 KiB windows per entry.

lvl3: [[PageDescriptor; 8192]; N],

/// Table descriptors, covering 512 MiB windows.

lvl2: [TableDescriptor; N],

}

/// Usually evaluates to 1 GiB for RPi3 and 4 GiB for RPi 4.

const ENTRIES_512_MIB: usize = bsp::memory::mmu::addr_space_size() >> FIVETWELVE_MIB_SHIFT;

/// The page tables.

///

/// # Safety

///

/// - Supposed to land in `.bss`. Therefore, ensure that they boil down to all "0" entries.

static mut TABLES: PageTables<{ ENTRIES_512_MIB }> = PageTables {

lvl3: [[PageDescriptor(0); 8192]; ENTRIES_512_MIB],

lvl2: [TableDescriptor(0); ENTRIES_512_MIB],

};

They are populated using bsp::memory::mmu::virt_mem_layout().get_virt_addr_properties() and a

bunch of utility functions that convert our own descriptors to the actual 64 bit integer entries

needed by the MMU hardware for the page table arrays.

Each page table has an entry (AttrIndex) that indexes into the MAIR_EL1 register, which holds

information about the cacheability of the respective page. We currently define normal cacheable

memory and device memory (which is not cached).

/// Setup function for the MAIR_EL1 register.

fn set_up_mair() {

// Define the memory types being mapped.

MAIR_EL1.write(

// Attribute 1 - Cacheable normal DRAM.

MAIR_EL1::Attr1_HIGH::Memory_OuterWriteBack_NonTransient_ReadAlloc_WriteAlloc

+ MAIR_EL1::Attr1_LOW_MEMORY::InnerWriteBack_NonTransient_ReadAlloc_WriteAlloc

// Attribute 0 - Device.

+ MAIR_EL1::Attr0_HIGH::Device

+ MAIR_EL1::Attr0_LOW_DEVICE::Device_nGnRE,

);

}

Afterwards, the Translation Table Base Register 0 - EL1 is set up with the base address of the

lvl2 tables and the Translation Control Register - EL1 is configured.

Finally, the MMU is turned on through the System Control Register - EL1. The last step also

enables caching for data and instructions.

link.ld

We need to align the ro section to 64 KiB so that it doesn't overlap with the next section that

needs read/write attributes. This blows up the binary in size, but is a small price to pay

considering that it reduces the amount of static paging entries significantly, when compared to the

classical 4 KiB granule.

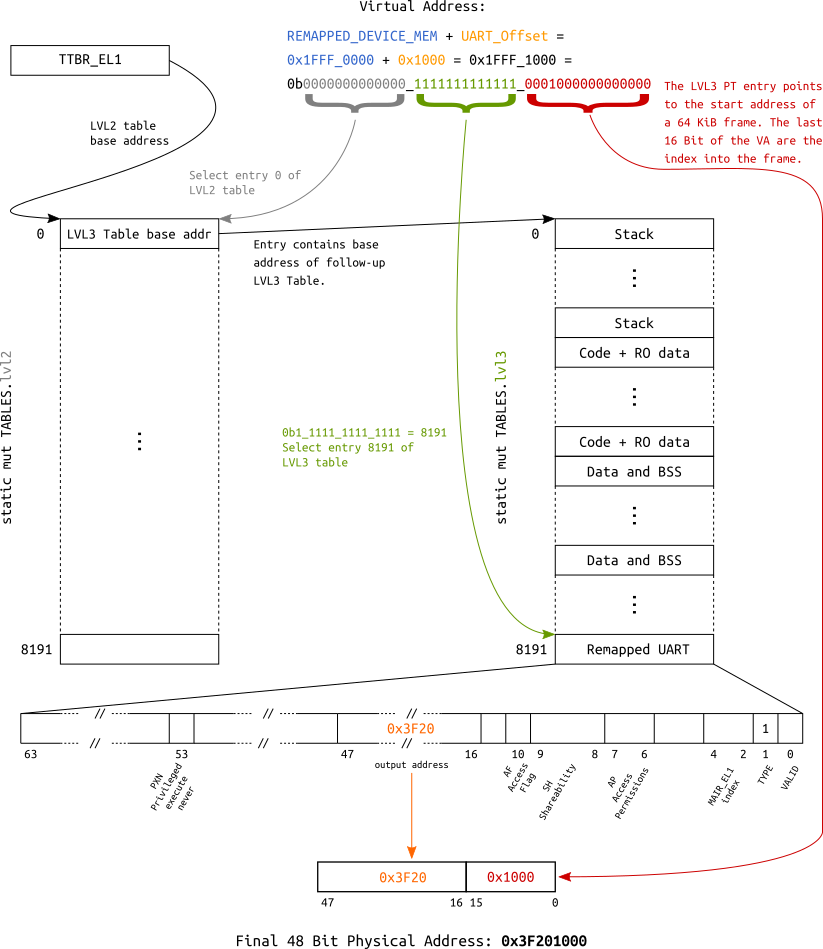

Address translation examples

For educational purposes, a layout is defined which allows to access the UART via two different

virtual addresses:

- Since we identity map the whole

Device MMIOregion, it is accessible by asserting its physical base address (0x3F20_1000or0xFA20_1000depending on which RPi you use) after theMMUis turned on. - Additionally, it is also mapped into the last

64 KiBentry of thelvl3table, making it accessible through base address0x1FFF_1000.

The following block diagram visualizes the underlying translation for the second mapping.

Address translation using a 64 KiB page descriptor

Zero-cost abstraction

The MMU init code is again a good example to see the great potential of Rust's zero-cost abstractions[1][2] for embedded programming.

Let's take a look again at the piece of code for setting up the MAIR_EL1 register using the

cortex-a crate:

/// Setup function for the MAIR_EL1 register.

fn set_up_mair() {

// Define the memory types being mapped.

MAIR_EL1.write(

// Attribute 1 - Cacheable normal DRAM

MAIR_EL1::Attr1_HIGH::Memory_OuterWriteBack_NonTransient_ReadAlloc_WriteAlloc

+ MAIR_EL1::Attr1_LOW_MEMORY::InnerWriteBack_NonTransient_ReadAlloc_WriteAlloc

// Attribute 0 - Device

+ MAIR_EL1::Attr0_HIGH::Device

+ MAIR_EL1::Attr0_LOW_DEVICE::Device_nGnRE,

);

}

This piece of code is super expressive, and it makes use of traits, different types and

constants to provide type-safe register manipulation.

In the end, this code sets the first four bytes of the register to certain values according to the data sheet. Looking at the generated code, we can see that despite all the type-safety and abstractions, it boils down to two assembly instructions:

00000000000815e0 <kernel::memory::mmu::arch_mmu::MemoryManagementUnit as kernel::memory::mmu::interface::MMU>::init::hed32b31a58c93b32:

...

8161c: mov w8, #0xff04

...

81644: msr MAIR_EL1, x8

Test it

$ make chainboot

[...]

Minipush 1.0

[MP] ⏳ Waiting for /dev/ttyUSB0

[MP] ✅ Connected

__ __ _ _ _ _

| \/ (_)_ _ (_) | ___ __ _ __| |

| |\/| | | ' \| | |__/ _ \/ _` / _` |

|_| |_|_|_||_|_|____\___/\__,_\__,_|

Raspberry Pi 3

[ML] Requesting binary

[MP] ⏩ Pushing 64 KiB ========================================🦀 100% 32 KiB/s Time: 00:00:02

[ML] Loaded! Executing the payload now

[ 3.085343] Booting on: Raspberry Pi 3

[ 3.086427] MMU online. Special regions:

[ 3.088339] 0x00080000 - 0x0008ffff | 64 KiB | C RO PX | Kernel code and RO data

[ 3.092422] 0x1fff0000 - 0x1fffffff | 64 KiB | Dev RW PXN | Remapped Device MMIO

[ 3.096375] 0x3f000000 - 0x4000ffff | 16 MiB | Dev RW PXN | Device MMIO

[ 3.099937] Current privilege level: EL1

[ 3.101848] Exception handling state:

[ 3.103629] Debug: Masked

[ 3.105192] SError: Masked

[ 3.106756] IRQ: Masked

[ 3.108320] FIQ: Masked

[ 3.109884] Architectural timer resolution: 52 ns

[ 3.112186] Drivers loaded:

[ 3.113532] 1. BCM GPIO

[ 3.114966] 2. BCM PL011 UART

[ 3.116660] Timer test, spinning for 1 second

[ !!! ] Writing through the remapped UART at 0x1FFF_1000

[ 4.120828] Echoing input now