Better Student Journalism

We pushed out the first version of the Open Journalism site in January. Our goal is for the site to be a place to teach students what they should know about journalism on the web. It should be fun too.

Topics like mapping, security, command line tools, and open source are all concepts that should be made more accessible, and should be easily understood at a basic level by all journalists. We’re focusing on students because we know student journalism well, and we believe that teaching maturing journalists about the web will provide them with an important lens to view the world with. This is how we got to where we are now.

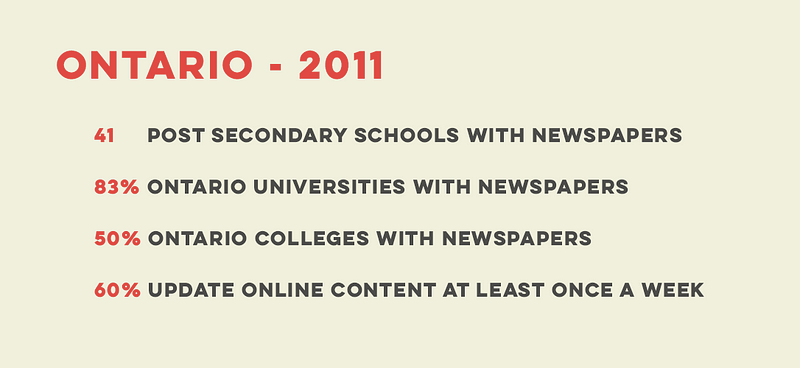

Circa 2011

In late 2011 I sat in the design room of our university’s student newsroom with some of the other editors: Kate Hudson, Brent Rose, and Nicholas Maronese. I was working as the photo editor then—something I loved doing. I was very happy travelling and photographing people while listening to their stories.

Photography was my lucky way of experiencing the many types of people my generation seemed to avoid, as well as many the public spends too much time discussing. One of my habits as a photographer was scouring sites like Flickr to see how others could frame the world in ways I hadn’t previously considered.

I started discovering beautiful things the web could do with images: things not possible with print. Just as every generation revolts against walking in the previous generations shoes, I found myself questioning the expectations that I came up against as a photo editor. In our newsroom the expectations were built from an outdated information world. We were expected to fill old shoes.

So we sat in our student newsroom—not very happy with what we were doing. Our weekly newspaper had remained essentially unchanged for 40+ years. Each editorial position had the same requirement every year. The big change happened in the 80s when the paper started using colour. We’d also stumbled into having a website, but it was updated just once a week with the release of the newspaper.

Information had changed form, but the student newsroom hadn’t, and it was becoming harder to romanticize the dusty newsprint smell coming from the shoes we were handed down from previous generations of editors. It was, we were told, all part of “becoming a journalist.”

We don’t know what we don’t know

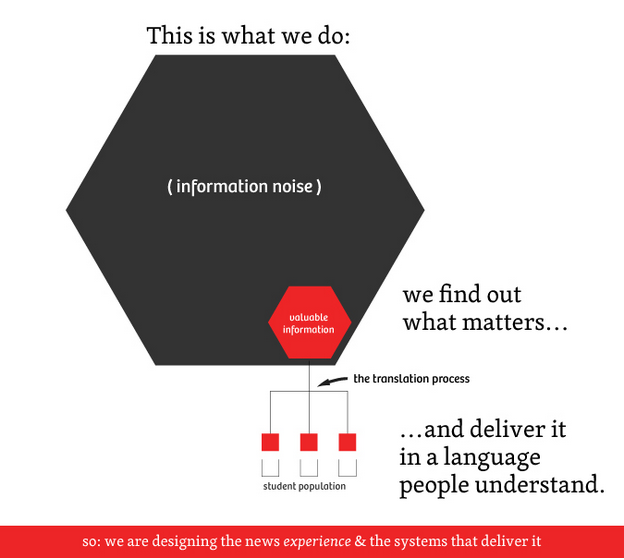

We spent much of the rest of the school year asking “what should we be doing in the newsroom?”, which mainly led us to ask “how do we use the web to tell stories?” It was a straightforward question that led to many more questions about the web: something we knew little about. Out in the real world, traditional journalists were struggling to keep their jobs in a dying print world. They wore the same design of shoes that we were supposed to fill. Being pushed to repeat old, failing strategies and blocked from trying something new scared us.

We had questions, so we started doing some research. We talked with student newsrooms in Canada and the United States, and filled too many Google Doc files with notes. Looking at the notes now, they scream of fear. We annotated our notes with naive solutions, often involving scrambled and immature odysseys into the future of online journalism.

There was a lot we didn’t know. We didn’t know how to build a mobile app. We didn’t know if we should build a mobile app. We didn’t know how to run a server. We didn’t know where to go to find a server. We didn’t know how the web worked. We didn’t know how people used the web to read news. We didn’t know what news should be on the web. If news is just information, what does that even look like?

We asked these questions to many students at other papers to get a consensus of what had worked and what hadn’t. They reported similar questions and fears about the web but followed with “print advertising is keeping us afloat so we can’t abandon it”.

In other words, we knew that we should be building a newer pair of shoes, but we didn’t know what the function of the shoes should be.

Common problems in student newsrooms (2011)

Our questioning of other student journalists in 15 student newsrooms brought up a few repeating issues.

- Lack of mentorship

- A news process that lacked consideration of the web

- No editor/position specific to the web

- Little exposure to many of the cool projects being put together by professional newsrooms

- Lack of diverse skills within the newsroom. Writers made up 95% of the personnel. Students with other skills were not sought because journalism was seen as “a career with words.” The other 5% were designers, designing words on computers, for print.

- Not enough discussion between the business side and web efforts

Common problems in student newsrooms (2013)

Two years later, we went back and looked at what had changed. We talked to a dozen more newsrooms and weren’t surprised by our findings.

- Still no mentorship or link to professional newsrooms building stories for the web

- Very little control of website and technology

- The lack of exposure that student journalists have to interactive storytelling. While some newsrooms are in touch with what’s happening with the web and journalism, there still exists a huge gap between the student newsroom and its professional counterpart

- No time in the current news development cycle for student newsrooms to experiment with the web

- Lack of skill diversity (specifically coding, interaction design, and statistics)

- Overly restricted access to student website technology. Changes are primarily visual rather than functional.

- Significantly reduced print production of many papers

- Computers aren’t set up for experimenting with software and code, and often locked down

Newsrooms have traditionally been covered in copies of The New York Times or Globe and Mail. Instead newsrooms should try spend at 20 minutes each week going over the coolest/weirdest online storytelling in an effort to expose each other to what is possible. “Hey, what has the New York Times R&D lab been up to this week?”

Instead of having computers that are locked down, try setting aside a few office computers that allow students to play and “break”, or encourage editors to buy their own Macbooks so they’re always able to practice with code and new tools on their own.

From all this we realized that changing a student newsroom is difficult. It takes patience. It requires that the business and editorial departments of the student newsroom be on the same (web)page. The shoes of the future must be different from the shoes we were given.

We need to rethink how long the new shoe design will be valid. It’s more important that we focus on the process behind making footwear than on actually creating a specific shoe. We shouldn’t be building a shoe to last 40 years. Our footwear design process will allow us to change and adapt as technology evolves. The media landscape will change, so having a newsroom that can change with it will be critical.

We are building a shoe machine, not a shoe.

A train or light at the end of the tunnel: are student newsrooms changing for the better?

In our 2013 research we found that almost 50% of student newsrooms had created roles specifically for the web. This sounds great, but is still problematic in its current state.

When a newsroom decides to create a position for the web, it’s often with the intent of having content flow steadily from writers onto the web. This is a big improvement from just uploading stories to the web whenever there is a print issue. However…

- The handoff

Problems arise because web editors are given roles that absolve the rest of the editors from thinking about the web. All editors should be involved in the process of story development for the web. While it’s a good idea to have one specific editor manage the website, contributors and editors should all play with and learn about the web. Instead of “can you make a computer do XYZ for me?”, we should be saying “can you show me how to make a computer do XYZ?” - Not just social media

A web editor could do much more than simply being in charge of the social media accounts for the student paper. Their responsibility could include teaching all other editors to be listening to what’s happening online. The web editor can take advantage of live information to change how the student newsroom reports news in real time. - Web (interactive) editor

The goal of having a web editor should be for someone to build and tell stories that take full advantage of the web as their medium. Too often the web’s interactivity is not considered when developing the story. The web then ends up as a resting place for print words.

Editors at newsrooms are still figuring out how to convince writers of the benefit to having their content online. There’s still a stronger draw to writers seeing their name in print than on the web. Showing writers that their stories can be told in new ways to larger audiences is a convincing argument that the web is a starting point for telling a story, not its graveyard.

When everyone in the newsroom approaches their website with the intention of using it to explore the web as a medium, they all start to ask “what is possible?” and “what can be done?” You can’t expect students to think in terms of the web if it’s treated as a place for print words to hang out on a web page.

We’re OK with this problem, if we see newsrooms continue to take small steps towards having all their editors involved in the stories for the web.

What we know

- New process

Our rough research has told us newsrooms need to be reorganized. This includes every part of the newsroom’s workflow: from where a story and its information comes from, to thinking of every word, pixel, and interaction the reader will have with your stories. If I was a photo editor that wanted to re-think my process with digital tools in mind, I’d start by asking “how are photo assignments processed and sent out?”, “how do we receive images?”, “what formats do images need to be exported in?”, “what type of screens will the images be viewed on?”, and “how are the designers getting these images?” Making a student newsroom digital isn’t about producing “digital manifestos”, it’s about being curious enough that you’ll want to to continue experimenting with your process until you’ve found one that fits your newsroom’s needs. - More (remote) mentorship

Lack of mentorship is still a big problem. Google’s fellowship program is great. The fact that it only caters to United States students isn’t. There are only a handful of internships in Canada where students interested in journalism can get experience writing code and building interactive stories. We’re OK with this for now, as we expect internships and mentorship over the next 5 years between professional newsrooms and student newsrooms will only increase. It’s worth noting that some of that mentorship will likely be done remotely. - Changing a newsroom culture

Skill diversity needs to change. We encourage every student newsroom we talk to, to start building a partnership with their school’s Computer Science department. It will take some work, but you’ll find there are many CS undergrads that love playing with web technologies, and using data to tell stories. Changing who is in the newsroom should be one of the first steps newsrooms take to changing how they tell stories. The same goes with getting designers who understand the wonderful interactive elements of the web and students who love statistics and exploring data. Getting students who are amazing at design, data, code, words, and images into one room is one of the coolest experience I’ve had. Everyone benefits from a more diverse newsroom.

What we don’t know

- Sharing curiosity for the web

We don’t know how to best teach students about the web. It’s not efficient for us to teach coding classes. We do go into newsrooms and get them running their first code exercises, but if someone wants to learn to program, we can only provide the initial push and curiosity. We will be trying out “labs” with a few schools next school year to hopefully get a better idea of how to teach students about the web. - Business

We don’t know how to convince the business side of student papers that they should invest in the web. At the very least we’re able to explain that having students graduate with their current skill set is painful in the current job market. - The future

We don’t know what journalism or the web will be like in 10 years, but we can start encouraging students to keep an open mind about the skills they’ll need. We’re less interested in preparing students for the current newsroom climate, than we are in teaching students to have the ability to learn new tools quickly as they come and go.