It took 15 days to end the mighty 20-year reign of Roger Ailes at Fox News, one of the most storied runs in media and political history. Ailes built not just a conservative cable news channel but something like a fourth branch of government; a propaganda arm for the GOP; an organization that determined Republican presidential candidates, sold wars, and decided the issues of the day for 2 million viewers. That the place turned out to be rife with grotesque abuses of power has left even its liberal critics stunned. More than two dozen women have come forward to accuse Ailes of sexual harassment, and what they have exposed is both a culture of misogyny and one of corruption and surveillance, smear campaigns and hush money, with implications reaching far wider than one disturbed man at the top.

It began, of course, with a lawsuit. Of all the people who might have brought down Ailes, the former Fox & Friends anchor Gretchen Carlson was among the least likely. A 50-year-old former Miss America, she was the archetypal Fox anchor: blonde, right-wing, proudly anti-intellectual. A memorable Daily Show clip showed Carlson saying she needed to Google the words czar and ignoramus. But television is a deceptive medium. Off-camera, Carlson is a Stanford- and Oxford-educated feminist who chafed at the culture of Fox News. When Ailes made harassing comments to her about her legs and suggested she wear tight-fitting outfits after she joined the network in 2005, she tried to ignore him. But eventually he pushed her too far. When Carlson complained to her supervisor in 2009 about her co-host Steve Doocy, who she said condescended to her on and off the air, Ailes responded that she was “a man hater” and a “killer” who “needed to get along with the boys.” After this conversation, Carlson says, her role on the show diminished. In September 2013, Ailes demoted her from the morning show Fox & Friends to the lower-rated 2 p.m. time slot.

Carlson knew her situation was far from unique: It was common knowledge at Fox that Ailes frequently made inappropriate comments to women in private meetings and asked them to twirl around so he could examine their figures; and there were persistent rumors that Ailes propositioned female employees for sexual favors. The culture of fear at Fox was such that no one would dare come forward. Ailes was notoriously paranoid and secretive — he built a multiroom security bunker under his home and kept a gun in his Fox office, according to Vanity Fair — and he demanded absolute loyalty from those who worked for him. He was known for monitoring employee emails and phone conversations and hiring private investigators. “Watch out for the enemy within,” he told Fox’s staff during one companywide meeting.

Taking on Ailes was dangerous, but Carlson was determined to fight back. She settled on a simple strategy: She would turn the tables on his surveillance. Beginning in 2014, according to a person familiar with the lawsuit, Carlson brought her iPhone to meetings in Ailes’s office and secretly recorded him saying the kinds of things he’d been saying to her all along. “I think you and I should have had a sexual relationship a long time ago, and then you’d be good and better and I’d be good and better. Sometimes problems are easier to solve” that way, he said in one conversation. “I’m sure you can do sweet nothings when you want to,” he said another time.

After more than a year of taping, she had captured numerous incidents of sexual harassment. Carlson’s husband, sports agent Casey Close, put her in touch with his lawyer Martin Hyman, who introduced her to employment attorney Nancy Erika Smith. Smith had won a sexual-harassment settlement in 2008 for a woman who sued former New Jersey acting governor Donald DiFranceso. “I hate bullies,” Smith told me. “I became a lawyer to fight bullies.” But this was riskier than any case she’d tried. Carlson’s Fox contract had a clause that mandated that employment disputes be resolved in private arbitration—which meant Carlson’s case could be thrown out and Smith herself could be sued for millions for filing.

Carlson’s team decided to circumvent the clause by suing Ailes personally rather than Fox News. They hoped that with the element of surprise, they would be able to prevent Fox from launching a preemptive suit that forced them into arbitration. The plan was to file in September 2016 in New Jersey Superior Court (Ailes owns a home in Cresskill, New Jersey). But their timetable was pushed up when, on the afternoon of June 23, Carlson was called into a meeting with Fox general counsel Dianne Brandi and senior executive VP Bill Shine, and fired the day her contract expired.* Smith, bedridden following surgery for a severed hamstring, raced to get the suit ready. Over the Fourth of July weekend, Smith instructed an IT technician to install software on her firm’s network and Carlson’s electronic devices to prevent the use of spyware by Fox. “We didn’t want to be hacked,” Smith said. They filed their lawsuit on July 6.

Carlson and Smith were well aware that suing Ailes for sexual harassment would be big news in a post-Cosby media culture that had become more sensitive to women claiming harassment; still, they were anxious about going up against such a powerful adversary. What they couldn’t have known was that Ailes’s position at Fox was already much more precarious than ever before.

When Carlson filed her suit, 21st Century Fox executive chairman Rupert Murdoch and his sons, James and Lachlan, were in Sun Valley, Idaho, attending the annual Allen & Company media conference. James and Lachlan, who were not fans of Ailes’s, had been taking on bigger and bigger roles in the company in recent years (technically, and much to his irritation, Ailes has reported to them since June 2015), and they were quick to recognize the suit as both a big problem — and an opportunity. Within hours, the Murdoch heirs persuaded their 85-year-old father, who historically has been loath to undercut Ailes publicly, to release a statement saying, “We take these matters seriously.” They also persuaded Rupert to hire the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison to conduct an internal investigation into the matter. Making things look worse for Ailes, three days after Carlson’s suit was filed, New York published the accounts of six other women who claimed to have been harassed by Ailes over the course of three decades.

A few hours after the New York report, Ailes held an emergency meeting with longtime friend Rudy Giuliani and lawyer Marc Mukasey at his home in Garrison, New York, according to a high-level Fox source. Ailes vehemently denied the allegations. The next morning, Ailes and his wife, Elizabeth, turned his second-floor office at Fox News into a war room. “It’s all bullshit! We have to get in front of this,” he said to executives. “This is not about money. This is about his legacy,” said Elizabeth, according to a Fox source. As part of his counteroffensive, Ailes rallied Fox News employees to defend him in the press. Fox & Friends host Ainsley Earhardt called Ailes a “family man”; Fox Business anchor Neil Cavuto wrote, reportedly of his own volition, an op-ed labeling Ailes’s accusers “sick.” Ailes’s legal team attempted to intimidate a former Fox correspondent named Rudi Bakhtiar who spoke to New York about her harassment.

Ailes told executives that he was being persecuted by the liberal media and by the Murdoch sons. According to a high-level source inside the company, Ailes complained to 21st Century Fox general counsel Gerson Zweifach that James, whose wife had worked for the Clinton Foundation, was trying to get rid of him in order to help elect Hillary Clinton. At one point, Ailes threatened to fly to France, where Rupert was vacationing with his wife, Jerry Hall, in an effort to save his job. Perhaps Murdoch told him not to bother, because the trip never happened.

According to a person close to the Murdochs, Rupert’s first instinct was to protect Ailes, who had worked for him for two decades. The elder Murdoch can be extremely loyal to executives who run his companies, even when they cross the line. (The most famous example of this is Sun editor Rebekah Brooks, whom he kept in the fold after the U.K. phone-hacking scandal.) Also, Ailes has made the Murdochs a lot of money — Fox News generates more than $1 billion annually, which accounts for 20 percent of 21st Century Fox’s profits — and Rupert worried that perhaps only Ailes could run the network so successfully. “Rupert is in the clouds; he didn’t appreciate how toxic an environment it was that Ailes created,” a person close to the Murdochs said. “If the money hadn’t been so good, then maybe they would have asked questions.”

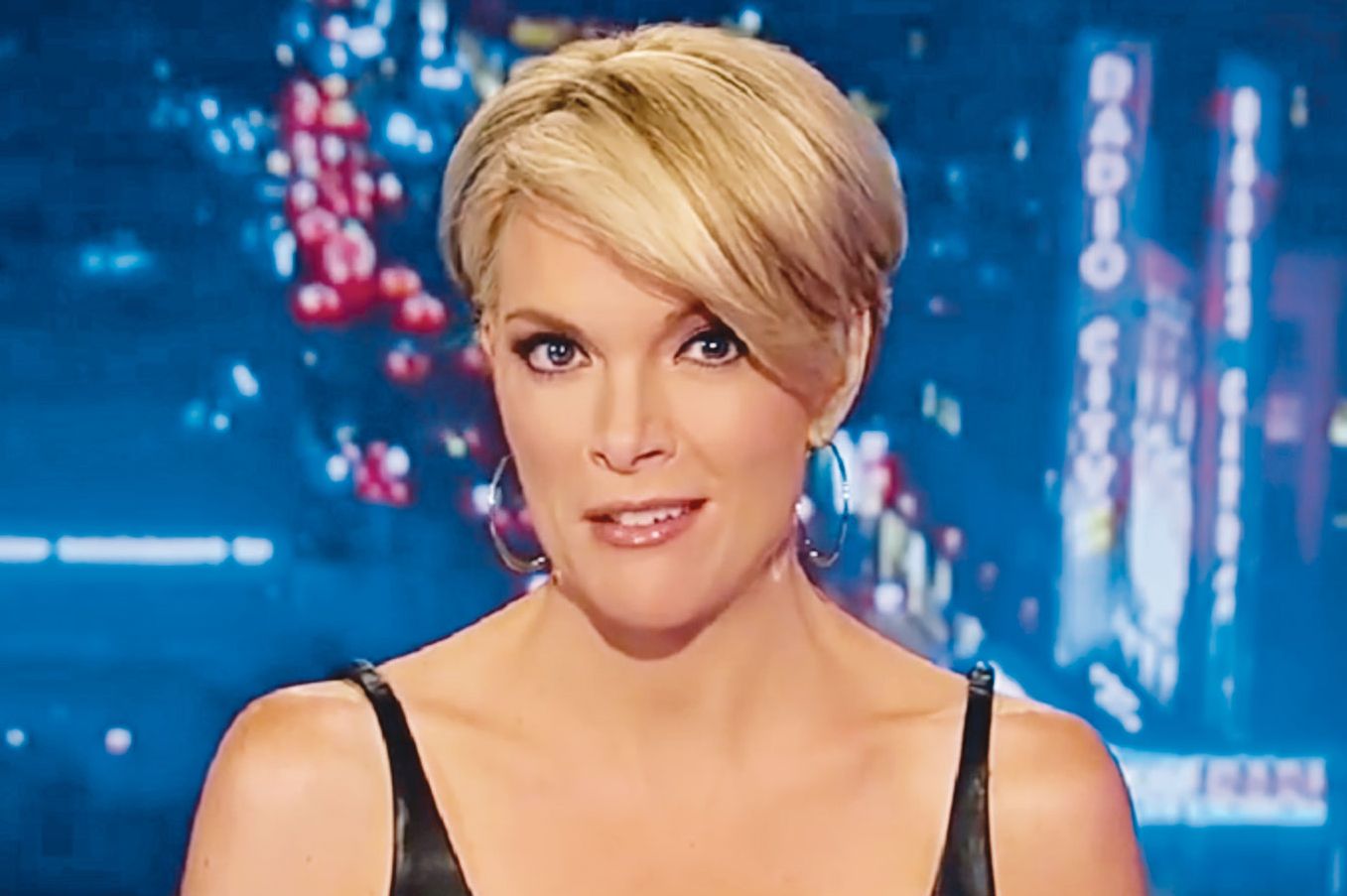

Beyond the James and Lachlan factor, the relationship between Murdoch and Ailes was becoming strained: Murdoch didn’t like that Ailes was putting Fox so squarely behind the candidacy of Donald Trump. And he had begun to worry less about whether Fox could endure without its creator. (In recent years, Ailes had taken extended health leaves from Fox and the ratings held.) Now Ailes had made himself a true liability: More than two dozen Fox News women told the Paul, Weiss lawyers about their harassment in graphic terms. The most significant of the accusers was Megyn Kelly, who is in contract negotiations with Fox and is considered by the Murdochs to be the future of the network. So important to Fox is Kelly that Lachlan personally approved her reported $6 million book advance from Murdoch-controlled publisher HarperCollins, according to two sources.

As the inevitability of an ouster became clear, chaos engulfed Ailes’s team. After news broke on the afternoon of July 19 that Kelly had come forward, Ailes’s lawyer Susan Estrich tried to send Ailes’s denial to Drudge but mistakenly emailed a draft of Ailes’s proposed severance deal, which Drudge, briefly, published instead. Also that day, Ailes’s allies claimed to conservative news site Breitbart that 50 of Fox’s biggest personalities were prepared to quit if Ailes was removed, though in reality there was no such pact. That evening, Murdoch used one of his own press organs to fire back, with the New York Post tweeting the cover of the next day’s paper featuring Ailes’s picture and news that “the end is near for Roger Ailes.”

Indeed, that evening Ailes was banned from Fox News headquarters, his company email and phone shut off. On the afternoon of July 21, a few hours before Trump was to accept the Republican nomination in Cleveland, Murdoch summoned Ailes to his New York penthouse to work out a severance deal. James had wanted Ailes to be fired for cause, according to a person close to the Murdochs, but after reviewing his contract, Rupert decided to pay him $40 million and retain him as an “adviser.” Ailes, in turn, agreed to a multiyear noncompete clause that prevents him from going to a rival network (but, notably, not to a political campaign). Murdoch assured Ailes that, as acting CEO of Fox News, he would protect the channel’s conservative voice. “I’m here, and I’m in charge,” Murdoch told Fox staffers later that afternoon with Lachlan at his side (James had gone to Europe on a business trip). That night, Rupert and Lachlan discussed the extraordinary turn of events over drinks at Eleven Madison Park.

The Murdochs must have hoped that by acting swiftly to remove Ailes, they had averted a bigger crisis. But over the coming days, harassment allegations from more women would make it clear that the problem was not limited to Ailes but included those who enabled him — both the loyal deputies who surrounded him at Fox News and those at 21st Century Fox who turned a blind eye. “Fox News masquerades as a defender of traditional family values,” claimed the lawsuit of Fox anchor Andrea Tantaros, who says she was demoted and smeared in the press after she rebuffed sexual advances from Ailes, “but behind the scenes, it operates like a sex-fueled, Playboy Mansion–like cult, steeped in intimidation, indecency and misogyny.”

Murdoch knew Ailes was a risky hire when he brought him in to start Fox News in 1996. Ailes had just been forced out as president of CNBC under circumstances that would foreshadow his problems at Fox.

While his volcanic temper, paranoia, and ruthlessness were part of what made Ailes among the best television producers and political operatives of his generation, those same attributes prevented him from functioning in a corporate environment. He hadn’t lasted in a job for more than a few years. “I have been through about 12 train wrecks in my career. Somehow, I always walk away,” he told an NBC executive.

By all accounts, Ailes had been a management disaster from the moment he arrived at NBC in 1993. But by 1995, things had reached a breaking point. In October of that year, NBC hired the law firm Proskauer Rose to conduct an internal investigation after then–NBC executive David Zaslav told human resources that Ailes had called him a “little fucking Jew prick” in front of a witness.

Zaslav told Proskauer investigators he feared for his safety. “I view Ailes as a very, very dangerous man. I take his threats to do physical harm to me very, very seriously … I feel endangered both at work and at home,” he said, according to NBC documents, which I first published in my 2014 biography of Ailes. CNBC executive Andy Friendly also filed complaints. “I along with several of my most talented colleagues have and continue to feel emotional and even physical fear dealing with this man every day,” he wrote. The Proskauer report chronicled Ailes’s “history of abusive, offensive, and intimidating statements/threats and personal attacks.” Ailes left NBC less than three months later.

What NBC considered fireable offenses, Murdoch saw as competitive advantages. He hired Ailes to help achieve a goal that had eluded Murdoch for a decade: busting CNN’s cable news monopoly. Back in the mid-’90s, no one thought it could be done. “I’m looking forward to squishing Rupert like a bug,” CNN founder Ted Turner boasted at an industry conference. But Ailes recognized how key wedge issues — race, religion, class — could turn conservative voters into loyal viewers. By January 2002, Fox News had surpassed CNN as the highest-rated cable news channel. But Ailes’s success went beyond ratings: The rise of Fox News provided Murdoch with the political influence in the United States that he already wielded in Australia and the United Kingdom. And by merging news, politics, and entertainment in such an overt way, Ailes was able to personally shape the national conversation and political fortunes as no one ever had before. It is not a stretch to argue that Ailes is largely responsible for, among other things, the selling of the Iraq War, the Swift-boating of John Kerry, the rise of the tea party, the sticking power of a host of Clinton scandals, and the purported illegitimacy of Barack Obama’s presidency.

Ailes became untouchable. At News Corp., he behaved just as he had at NBC, but Murdoch tolerated Ailes’s abusiveness because he was pleased with the results.

Ailes used Fox’s payroll as a patronage tool, doling out jobs to Republican politicians, friends, and political operatives. He made his personal lawyer, Peter Johnson Jr., a regular guest on Fox shows, despite producers’ misgivings about Johnson’s on-air performance. (They nicknamed Johnson “The Must-Do.”) Manny Alvarez, whose daughter went to school with Ailes’s son, became a medical commentator.

Ailes also positioned his former secretaries in key departments where he could make use of their loyalty to him. One, Nikole King, went to the finance department, where she handled Ailes’s personal expenses, a Fox executive said. Another, Brigette Boyle, went to human resources, where she was “tasked with hiring the ‘right’ people,” a former executive recalled.

But most striking is the extent to which Ailes ruled Fox News like a surveillance state. According to executives, he instructed Fox’s head of engineering, Warren Vandeveer, to install a CCTV system that allowed Ailes to monitor Fox offices, studios, greenrooms, the back entrance, and his homes. When Ailes spotted James Murdoch on the monitor smoking a cigarette outside the office, he remarked to his deputy Bill Shine, “Tell me that mouth hasn’t sucked a cock,” according to an executive who was in the room; Shine laughed. (A Fox spokesperson said Shine did not recall this.) Fox’s IT department also monitored employee email, according to sources. When I asked Fox’s director of IT, Deborah Sadusingh, about email searches, she said, “I can’t remember all the searches I’ve done.”

When Ailes uncovered something he didn’t like, he had various means of retaliation and increased surveillance. Fox’s notorious PR department, which for years was directed by Brian Lewis and is now overseen by Irena Briganti, was known for leaking negative stories about errant employees to journalists. Fox contributor Jim Pinkerton wrote an anonymous blog called the Cable Game that attacked Ailes-selected targets, two Fox executives confirmed. Fox contributor Bo Dietl did private-investigation work for Ailes, including following former Fox producer Andrea Mackris after she sued Bill O’Reilly for sexual harassment, a Fox source said. Ailes turned these same tactics on his enemies outside the company, including journalists. CNN’s Brian Stelter recently reported on Fox’s 400-page opposition-research file on me.

Fox News also obtained the phone records of journalists, by legally questionable means. According to two sources with direct knowledge of the incident, Brandi, Fox’s general counsel, hired a private investigator in late 2010 to obtain the personal home- and cell-phone records of Joe Strupp, a reporter for the liberal watchdog group Media Matters. (Through a spokesperson, Brandi denied this.) In the fall of that year, Strupp had written several articles quoting anonymous Fox sources, and the network wanted to determine who was talking to him. “This was the culture. Getting phone records doesn’t make anybody blink,” one Fox executive told me.

What makes this practice all the more brazen is that the Guardian was already publishing articles about phone-hacking at Murdoch’s British newspaper division. About that scandal, Murdoch said, “I do not accept ultimate responsibility. I hold responsible the people that I trusted to run it and the people they trusted.” In this case, of course, the person he trusted, inexplicably, was Ailes, and Murdoch does not seem to have wanted to know how Ailes chose to spend company funds. Every year, Murdoch approved Ailes’s budgets without question. “When you have an organization making that much money, we didn’t go line by line through people’s budgets,” a former News Corp. executive said.

Ailes was born in May 1940 in Warren, Ohio, then a booming industrial town. His father, a factory foreman, abused his wife and two sons. “He did like to beat the shit out of you with that belt … It was a pretty routine fixture of childhood,” Ailes’s brother Robert told me when I was reporting my book. His parents divorced in 1960. In court papers, Ailes’s mother alleged that her husband “threatened her life and to do her physical harm.”

Perhaps as an escape, Ailes lost himself in television. He suffered from hemophilia and was often homebound from school, so he spent hours on the living-room couch watching variety shows and Westerns. “He analyzed it, and he figured it out,” his brother told me of Ailes’s fascination with TV.

After graduating from Ohio University in 1962, Ailes landed a job as a gofer on The Mike Douglas Show, a daytime variety program that at the time was broadcast from Cleveland. Within four years, he had muscled aside the show’s creator and more seasoned colleagues to become the executive producer. Ailes’s mentor at The Mike Douglas Show, Chet Collier, who would later serve as his deputy at Fox, drilled into him the notion that television is a visual medium. “I’m not hiring talent for their brainpower,” Collier would say.

Though Ailes had married his college girlfriend, he used his growing power to take advantage of the parade of beautiful women coming through his office hoping to be cast on the show. Over the past two months, I interviewed 18 women who shared accounts of Ailes’s offering them job opportunities if they would agree to perform sexual favors for him and for his friends. In some cases, he threatened to release tapes of the encounters to prevent the women from reporting him. “The feeling I got in the interview was repulsion, power-hungriness, contempt, violence, and the need to subjugate and humiliate,” says a woman who auditioned for Ailes in 1968 when she was a college student.

In August 1968, Ailes left The Mike Douglas Show to join Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign as a media strategist. Ailes’s success in reinventing the candidate for television helped propel Nixon to the White House and made Ailes a media star (he was the anti-hero of Joe McGinniss’s landmark book The Selling of the President). But even back then, Ailes’s recklessness put his thriving career at risk. A former model told me that her parents called the police on Ailes after she told them he assaulted her in a Cincinnati hotel room in 1969. “I remember Ailes sweet-talking my parents out of pressing charges,” she says.

One prominent Republican told me that it was Ailes’s well-known reputation for awful behavior toward women that prevented him from being invited to work in the Nixon White House (or, later, in the administration of Bush 41). So after the ’68 election, he moved to New York, where he continued to use his power to demand sex from women seeking career opportunities. During this time Ailes divorced, remarried, and divorced again. A former television producer described an interview with Ailes in 1975, in which he said: “If you want to make it in New York City in the TV business, you’re going to have to fuck me, and you’re going to do that with anyone I tell you to.” While running media strategy on Rudy Giuliani’s 1989 mayoral campaign, Ailes propositioned an employee of his political-consulting firm: He name-dropped his friend Barry Diller and said that if she’d have sex with him he’d ask Diller to get her a part on Beverly Hills 90210. (Diller said he never received such a request.)

In 1998, two years after launching Fox, Ailes got married for the third time, to a woman named Elizabeth Tilson, a 37-year-old producer who had worked for him at CNBC. Two years later, when Ailes was 59, the couple had a son. But neither a new marriage nor parenthood changed his predatory behavior toward the women who worked for him.

According to interviews with Fox News women, Ailes would often begin by offering to mentor a young employee. He then asked a series of personal questions to expose potential vulnerabilities. “He asked, ‘Am I in a relationship? What are my familial ties?’ It was all to see how stable or unstable I was,” said a former employee. Megyn Kelly told lawyers at Paul, Weiss that Ailes made an unwanted sexual advance toward her in 2006 when she was going through a divorce. A lawyer for former anchor Laurie Dhue told me that Ailes harassed her around 2006; at the time, she was struggling with alcoholism.

Ailes’s longtime executive assistant Judy Laterza — who became one of his top lieutenants, earning more than $2 million a year, according to a Fox executive — seemed to function as a recruiter of sorts. According to Carlson’s attorney, in 2002, Laterza remarked to a college intern she saw on the elevator about how pretty she was and invited her to meet Ailes. After that meeting, Ailes arranged for the young woman to transfer to his staff. Her first assignment was to go down to the newsstand and fetch him the latest issue of Maxim. When she returned with the magazine, Ailes asked her to stay with him in his office. He flipped through the pages. The woman told the Washington Post that Ailes said, “You look like the women in here. You have great legs. If you sleep with me, you could be a model or a newscaster.” She cut short her internship. (Laterza did not respond to a request for comment.)

I spoke with another Fox News administrative assistant who said Laterza invited her to meet Ailes in 2004. The woman, then 25, told Ailes that her ambition was to do commercials. Ailes offered to pay for voice lessons (she declined) and helped her land an agent at William Morris. A few months later, Ailes summoned her to his office for an update. She told him how excited she was about the opportunities, and Ailes invited her for a drink. She suggested happy hour, but he demurred. “For a man in my position, it would have to be alone at a hotel,” she recalls him saying. “Do you know how to play the game?” She tried to get out of the situation as tactfully as possible. “I don’t feel comfortable doing this,” she said. “I respect your family; what about your son?” She remembers Ailes’s reply: “I’m a multifaceted man. That’s one side of me.” As she left the office, she says, Ailes tried to kiss her. “I was holding a binder full of voice-over auditions that I put between us. I was terrified.” She says she never heard from the William Morris agent again.

The fact that these incidents of harassment were so common may have contributed to why no one at Fox came forward or filed a lawsuit until now. Ailes’s attitudes about women permeated the very air of the network, from the exclusive hiring of attractive women to the strictly enforced skirts-and-heels dress code to the “leg cam” that lingers on female panelists’ crossed legs on air. It was hard to complain about something that was so normalized. Other senior executives harassed women, too. “Anyone who claimed there was a hostile work environment was seen as a complainer,” says a former Fox employee who says Ailes harassed her. “Or that they can’t take a joke.”

It is unfathomable to think, given Ailes’s reputation, given the number of women he propositioned and harassed and assaulted over decades, that senior management at Fox News was unaware of what was happening. What is more likely is that their very jobs included enabling, abetting, protecting, and covering up for their boss. “No one said no to Roger,” a Fox executive said.

The story of Laurie Luhn, which I reported in July, is an example of how Ailes used Fox’s public-relations, legal, and finance departments to facilitate his behavior. Ailes met Luhn on the 1988 George H.W. Bush campaign, and soon thereafter he put her on a $500 monthly retainer with his political-consulting firm to be his “spy” in Washington, though really her job was to meet him in hotel rooms. (During their first encounter, Luhn says, Ailes videotaped her in a garter belt and told her: “I am going to put [the tape] in a safe-deposit box just so we understand each other.”) Ailes recruited Luhn to Fox in 1996, before the network even launched. Collier, then his deputy, offered her a job in guest relations in the Washington bureau.

Laterza, Shine, and Shine’s deputy Suzanne Scott would take turns summoning Luhn for “meetings” in New York. (A Fox spokesperson said executives were not aware Ailes was sexually involved with Luhn.) Ailes and Luhn would meet in the afternoons, Luhn said, at hotels near Times Square, and Ailes paid her cash for sexual favors. She was also on the payroll at Fox — at her peak, she earned $250,000 a year as an event planner for the channel; multiple sources confirmed that she was a “Friend of Roger,” with special protection within the company. But the arrangement required her to do many things that now cause her anguish, including luring young female Fox employees into one-on-one meetings with Ailes that Luhn knew would likely result in harassment. “You’re going to find me ‘Roger’s Angels,’ ” he reportedly told her. One of Luhn’s employees received a six-figure settlement after filing a harassment claim against Ailes.

By the fall of 2006, Luhn says, Ailes was worried that she might go public with her story or cause a scene of some kind. That’s when the Fox machine really kicked into gear. According to Luhn, Fox PR tried to spread a rumor to the New York Daily News that Luhn had had an affair with Lee Atwater (which she denies), a story designed to make Luhn seem promiscuous so that her credibility would be damaged. When Luhn had an emotional breakdown en route to a vacation in Mexico, it was Shine’s job to arrange to bring her home. Scott picked her up at the airport and drove her to the Warwick Hotel on Sixth Avenue, where Luhn recalls that Scott checked her in under Scott’s name. (Scott denies this.)

Luhn later moved into a Fox corporate apartment in Chelsea, during which time, she says, Laterza and Shine monitored her email. (Shine denies this.) Luhn’s father says that Shine called him several times to check up on Luhn after she moved to California while still on the Fox payroll. Eventually, Shine even recommended a psychiatrist, who medicated and hospitalized her. At one point, Luhn attempted suicide. Through a spokesperson, Shine says he “was only trying to help.”

In late 2010 or early 2011, Luhn wrote a letter to Brandi, the Fox lawyer, saying she had been sexually harassed by Ailes for 20 years. According to a source, Brandi asked Ailes about the allegations, which he denied. Brandi then worked out a settlement at Ailes’s request. On June 15, 2011, Luhn signed a $3.15 million settlement agreement with extensive nondisclosure provisions. The payment was approved by Fox News CFO Mark Kranz. The check, which I viewed, was signed by David E. Miller, a treasurer for Fox Television Stations, Inc., a division run by current Fox co-president Jack Abernethy. “I have no idea how my name ended up on the check,” says Miller, citing standard company practice of signing checks and not asking questions. The settlement documents, which Luhn also showed me, were signed by Ailes, Brandi, and Shine.

After Luhn left Fox, Ailes took additional measures to conceal his harassment of employees. In 2011, he installed a floor-to-ceiling wooden door outside his executive suite. Only his assistants could see who entered his office. According to a former Fox producer, Laterza entered fake names into Ailes’s datebook when women went into his office: “If you got ahold of his ledger, you would not know who visited him.”

Still, the whispers about Ailes and women were growing louder. Karem Alsina, a former Fox makeup artist, told me she grew suspicious when Fox anchors came to see her before private meetings with Ailes to have their makeup done. “They would say, ‘I’m going to see Roger, gotta look beautiful!’ ” she recalled. “One of them came back down after a meeting, and the makeup on her nose and chin was gone.”

In 2012, after I had been reporting my Ailes biography for a year, Megyn Kelly became so concerned about the rumors that she went to Ailes’s then–PR chief, Brian Lewis, and attempted an intervention, according to a person close to Kelly. She told Lewis that Ailes was being reckless and that I might include his behavior in my book. (I did report the stories of two women who claimed Ailes had harassed them earlier in his career, and though I heard rumors of Ailes and Fox News women, I could not confirm them at the time.) Lewis, according to the source, asked Laterza to tell Ailes to stop because he thought Ailes might listen to his longtime assistant. Instead, according to the source, Laterza told Ailes that his PR chief was being disloyal. Less than a year later, Ailes fired Lewis.

Megyn Kelly was not a household name when she started at Fox News in 2004. A former corporate lawyer, she landed at Fox when former Special Report anchor Brit Hume recommended her to Ailes. She still wasn’t well known in 2006, when she got divorced and Ailes tried to take advantage of her perceived vulnerability. She may not have been any more powerful, at the time, than the other women he preyed on, but she was one of the lucky ones: She managed to rebuff his sexual overtures in a way that didn’t alienate her boss. “She was able to navigate the relationship to a professional place,” a person close to Kelly told me. In fact, Kelly’s career flourished after this. In 2010, Ailes gave her a two-hour midday show, on which she enthusiastically fanned his right-wing agenda — for instance, hyping stories about the New Black Panthers that many thought were racist. In October 2013, Ailes promoted Kelly to Sean Hannity’s 9 p.m. prime-time slot, where she memorably declared that Jesus and Santa are “white.” When asked by a fan on Twitter to name her biggest influence, she responded, “Roger Ailes.”

By 2015, although her show was still reliably right-wing, Kelly’s brand was evolving. After several high-profile clashes with Republican men, including Dick Cheney, she was developing something of a reputation as a feminist. As she entered the final two years of her contract, she started to think about a future outside of Fox, meeting with CNN chief Jeff Zucker in 2013.

Then came Donald Trump. Kelly’s feud with the GOP nominee was one of the dominant story lines of the presidential election; it also exploded the fragile balance of relationships at the top of Fox News.

According to Fox sources, Murdoch blamed Ailes for laying the groundwork for Trump’s candidacy. Ailes had given Trump, his longtime friend, a weekly call-in segment on Fox & Friends to sound off on political issues. (Trump used Fox News to mainstream the birther conspiracy theory.) Ailes also had lunch with Trump days before he launched his presidential campaign and continued to feed him political advice throughout the primaries, according to sources close to Trump and Ailes. (And in the days after Carlson filed her lawsuit, Trump advised Ailes on navigating the crisis, even recommending a lawyer.)

Murdoch was not a fan of Trump’s and especially did not like his stance on immigration. (The antipathy was mutual: “Murdoch’s been very bad to me,” Trump told me in March.) A few days before the first GOP debate on Fox in August 2015, Murdoch called Ailes at home. “This has gone on long enough,” Murdoch said, according to a person briefed on the conversation. Murdoch told Ailes he wanted Fox’s debate moderators — Kelly, Bret Baier, and Chris Wallace — to hammer Trump on a variety of issues. Ailes, understanding the GOP electorate better than most at that point, likely thought it was a bad idea. “Donald Trump is going to be the Republican nominee,” Ailes told a colleague around this time. But he didn’t fight Murdoch on the debate directive.

On the night of August 6, in front of 24 million people, the Fox moderators peppered Trump with harder-hitting questions. But it was Kelly’s question regarding Trump’s history of crude comments about women that created a media sensation. He seemed personally wounded by her suggestion that this spoke to a temperament that might not be suited for the presidency. “I’ve been very nice to you, though I could probably maybe not be based on the way you have treated me,” he said pointedly.

After the debate, Trump called Ailes and screamed about Kelly. “How could you do this?” he said, according to a person briefed on the call. Ailes was caught between his friend Trump, his boss Murdoch, and his star Kelly. “Roger lost control of Megyn and Trump,” a Fox anchor said.

The parties only became more entrenched when Trump launched a series of attacks against Kelly, including suggesting that her menstrual cycle had influenced her debate question. Problematically for Ailes, Fox’s audience took Trump’s side in the fight; Kelly received death threats from viewers, according to a person close to her. Kelly had even begun to speculate, according to one Fox source, that Trump might have been responsible for her getting violently ill before the debate last summer. Could he have paid someone to slip something into her coffee that morning in Cleveland? she wondered to colleagues.

While Ailes released a statement defending Kelly, he privately blamed her for creating the crisis. “It was an unfair question,” he told a Fox anchor. Kelly felt betrayed, both by Ailes and by colleagues like O’Reilly and Baier when they didn’t defend her, sources who spoke with her said. “She felt she put herself out there,” a colleague said.

Frustrated at Fox, Kelly hired a powerhouse agent at CAA and began auditioning in earnest, and in public, for a job at another network. In interviews, she said her ambition was to become the next Barbara Walters and to host prime-time specials. She wanted to prove to the industry she could land a “big get” — and the biggest get of all was Trump. So Kelly went to Trump Tower to lobby the candidate for an interview. It worked — even Trump couldn’t resist the spectacle of a rematch — but in the end the show failed: The ratings were terrible and reviewers panned her generally sycophantic questions. Worse for Kelly, it eroded her burgeoning status as a tough journalist who stood up to Trump. Afterward, her relationship with Ailes further deteriorated. According to Fox sources, they barely spoke in recent months.

Kelly and Gretchen Carlson were not friends or allies, but Carlson’s lawsuit presented an opportunity. Kelly could bust up the boys’ club at Fox, put herself on the right side of a snowballing media story, and rid herself of a boss who was no longer supportive of her — all while maximizing her leverage in a contract negotiation. She also had allies in the Murdoch sons. According to a source, Kelly told James Murdoch that Ailes had made harassing comments and inappropriately hugged her in his office. James and Lachlan both encouraged her to speak to the Paul, Weiss lawyers about it. Kelly was only the third or fourth woman to speak to the lawyers, according to a source briefed on the inquiry, but she was by far the most important. After she spoke with investigators, and made calls to current and former Fox colleagues to encourage them to speak to Paul, Weiss as well, many more women came forward.

Ailes was furious with Kelly for not defending him publicly. According to a Fox source, Ailes’s wife Elizabeth wanted Fox PR to release racy photos of Kelly published years ago in GQ as a way of discrediting her. The PR department, in this instance, refused. (Elizabeth is said to be taking all of the revelations especially hard, according to four sources close to the family. Giuliani, who officiated their wedding, told Murdoch she would likely divorce Ailes, according to two sources: “This marriage won’t last,” he said.)

Two days after New York reported that Kelly had told her story to Paul, Weiss attorneys, Ailes was gone. And Kelly had made herself more important to the network than ever.

Ailes’s ouster has created a leadership vacuum at Fox News. Several staffers have described feeling like being part of a totalitarian regime whose dictator has just been toppled. “No one knows what to do. No one knows who to report to. It’s just mayhem,” said a Fox host. As details of the Paul, Weiss investigation have filtered through the offices, staffers are expressing a mixture of shock and disgust. The scope of Ailes’s alleged abuse far exceeds what employees could have imagined. “People are so devastated,” one senior executive said. Those I spoke with have also been unnerved by Shine and Brandi’s roles in covering up Ailes’s behavior.

Despite revelations of how Ailes’s management team enabled his harassment, Murdoch has so far rejected calls — including from James, according to sources — to conduct a wholesale housecleaning. On August 12, Murdoch promoted Shine and another Ailes loyalist, Jack Abernethy, to become co-presidents of Fox News. He named Scott executive vice-president and kept Brandi and Briganti in their jobs. Fox News’s chief financial officer, Mark Kranz, is the only senior executive to have been pushed out (officially he retired), along with Laterza and a handful of assistants, contributors, and consultants. “Of course, they are trying to isolate this to just a few bad actors,” a 21st Century Fox executive told me.

Many people I spoke with believe that the current management arrangement is just a stopgap until the election. “As of November 9, there will be a bloodbath at Fox,” predicts one host. “After the election, the prime-time lineup could be eviscerated. O’Reilly’s been talking about retirement. Megyn could go to another network. And Hannity will go to Trump TV.”

The prospect of Trump TV is a source of real anxiety for some inside Fox. The candidate took the wedge issues that Ailes used to build a loyal audience at Fox News — especially race and class — and used them to stoke barely containable outrage among a downtrodden faction of conservatives. Where that outrage is channeled after the election — assuming, as polls now suggest, Trump doesn’t make it to the White House — is a big question for the Republican Party and for Fox News. Trump had a complicated relationship with Fox even when his good friend Ailes was in charge; without Ailes, it’s plausible that he will try to monetize the movement he has galvanized in competition with the network rather than in concert with it. Trump’s appointment of Steve Bannon, chairman of Breitbart, the digital-media upstart that has by some measures already surpassed Fox News as the locus of conservative energy, to run his campaign suggests a new right-wing news network of some kind is a real possibility. One prominent media executive told me that if Trump loses, Fox will need to try to damage him in the eyes of its viewers by blaming him for the defeat.

Meanwhile, the Murdochs are looking for a permanent CEO to navigate these post-Ailes, Trump-roiled waters. According to sources, James’s preferred candidates include CBS president David Rhodes (though he is under contract with CBS through 2019); Jesse Angelo, the New York Post publisher and James’s Harvard roommate; and perhaps a television executive from London. Sources say Lachlan, who politically is more conservative than James, wants to bring in an outsider. Rupert was seen giving Rebekah Brooks a tour of the Fox offices several months ago, creating speculation that she could be brought in to run Fox. Another contender is Newsmax CEO Chris Ruddy.

As for the women who collectively brought an end to the era of Roger Ailes, their fortunes are mixed. Megyn Kelly is in a strong position in her contract talks, and sources say Gretchen Carlson will soon announce an eight-figure settlement. But because New York has a three-year statute of limitations on sexual harassment, so far just two women in addition to Carlson are said to be receiving settlements from 21st Century Fox. The many others who left or were forced out of the company before the investigation came away with far less — in some cases nothing at all.

It’s hard to say that justice has been served. But the story isn’t over: Last week, the shareholder law firm Scott & Scott announced it was investigating 21st Century Fox to “determine whether Fox’s Officers and Directors have breached their fiduciary duties.” Meanwhile, Ailes is walking away from his biggest career train wreck yet, seeking relevance and renewed power through the one person in the country who doesn’t see him as political kryptonite, the candidate he created: Donald J. Trump. Ailes may be trying to sell us another president, but now we know the truth about the salesman.

*This sentence has been updated to reflect Shine’s presence at the meeting, a detail that was confirmed after publication.

*This article appears in the September 5, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.

*An earlier version of the article inaccurately stated Manny Alvarez is Elizabeth Ailes’s doctor.