|

|

5 years ago | |

|---|---|---|

| .. | ||

| README.md | 5 years ago | |

| forest.png | 5 years ago | |

| instance_texture.png | 5 years ago | |

| instance_texture_scaled.png | 5 years ago | |

| instance_texture_scaled.xcf | 5 years ago | |

README.md

Instancing

Up to this point we've been drawing just one object. Most games have hundreds of objects on screen at the same time. If we wanted to draw multiple instances of our model, we could copy the vertex buffer and modify it's vertices to be in the right place, but this would be hilariously inefficient. We have our model, and we now how to position it in 3d space with a matrix, like we did the camera, so all we have to do is change the matrix we're using when we draw.

The naive method

First let's modify Uniforms to include a model property.

#[repr(C)]

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct Uniforms {

view_proj: cgmath::Matrix4<f32>,

model: cgmath::Matrix4<f32>, // NEW!

}

impl Uniforms {

fn new() -> Self {

use cgmath::SquareMatrix;

Self {

view_proj: cgmath::Matrix4::identity(),

model: cgmath::Matrix4::identity(), // NEW!

}

}

fn update_view_proj(&mut self, camera: &Camera) {

self.view_proj = OPENGL_TO_WGPU_MATRIX * camera.build_view_projection_matrix();

}

}

With that let's introduce another struct for our instances. We'll use it to store the position and rotation of our instances. We'll also have a method to convert our instance data into a matrix that we can give to Uniforms.

struct Instance {

position: cgmath::Vector3<f32>,

rotation: cgmath::Quaternion<f32>,

}

impl Instance {

fn to_matrix(&self) -> cgmath::Matrix4<f32> {

cgmath::Matrix4::from_translation(self.position)

* cgmath::Matrix4::from(self.rotation)

}

}

Next we'll add instances: Vec<Instance>, to State and create our instances in new with the following in new().

// ...

// add these at the top of the file

const NUM_INSTANCES_PER_ROW: u32 = 10;

const NUM_INSTANCES: u32 = NUM_INSTANCES_PER_ROW * NUM_INSTANCES_PER_ROW;

const INSTANCE_DISPLACEMENT: cgmath::Vector3<f32> = cgmath::Vector3::new(NUM_INSTANCES_PER_ROW as f32 * 0.5, 0.0, NUM_INSTANCES_PER_ROW as f32 * 0.5);

// make a 10 by 10 grid of objects

let instances = (0..NUM_INSTANCES_PER_ROW).flat_map(|z| {

(0..NUM_INSTANCES_PER_ROW).map(move |x| {

let position = cgmath::Vector3 { x: x as f32, y: 0.0, z: z as f32 } - INSTANCE_DISPLACEMENT;

let rotation = if position.is_zero() {

// this is needed so an object at (0, 0, 0) won't get scaled to zero

// as Quaternions can effect scale if they're not create correctly

cgmath::Quaternion::from_axis_angle(cgmath::Vector3::unit_z(), cgmath::Deg(0.0))

} else {

cgmath::Quaternion::from_axis_angle(position.clone().normalize(), cgmath::Deg(45.0))

};

Instance {

position, rotation,

}

})

}).collect();

// ...

Self {

// ...

instances,

}

Now that that's done, we need to update shader.vert to use the model matrix passed in through Uniforms.

#version 450

layout(location=0) in vec3 a_position;

layout(location=1) in vec2 a_tex_coords;

layout(location=0) out vec2 v_tex_coords;

layout(set=1, binding=0)

uniform Uniforms {

mat4 u_view_proj;

mat4 u_model; // NEW!

};

void main() {

v_tex_coords = a_tex_coords;

gl_Position = u_view_proj * u_model * vec4(a_position, 1.0); // UPDATED!

}

If you run the program now, you won't see anything different. That's because we aren't actually updating the uniform buffer at all. Using our current method, we need to update the uniform buffer for every instance we draw. We'll do this in render() with something like the following.

for instance in &self.instances {

// 1.

self.uniforms.model = instance.to_matrix();

let staging_buffer = self.device

.create_buffer_mapped(1, wgpu::BufferUsage::COPY_SRC)

.fill_from_slice(&[self.uniforms]);

encoder.copy_buffer_to_buffer(&staging_buffer, 0, &self.uniform_buffer, 0, std::mem::size_of::<Uniforms>() as wgpu::BufferAddress);

// 2.

let mut render_pass = encoder.begin_render_pass(&wgpu::RenderPassDescriptor {

color_attachments: &[

wgpu::RenderPassColorAttachmentDescriptor {

attachment: &frame.view,

resolve_target: None,

load_op: wgpu::LoadOp::Load, // 3.

store_op: wgpu::StoreOp::Store,

clear_color: wgpu::Color {

r: 0.1,

g: 0.2,

b: 0.3,

a: 1.0,

},

}

],

depth_stencil_attachment: None,

});

render_pass.set_pipeline(&self.render_pipeline);

render_pass.set_bind_group(0, &self.diffuse_bind_group, &[]);

render_pass.set_bind_group(1, &self.uniform_bind_group, &[]);

render_pass.set_vertex_buffers(0, &[(&self.vertex_buffer, 0)]);

render_pass.set_index_buffer(&self.index_buffer, 0);

render_pass.draw_indexed(0..self.num_indices, 0, 0..1);

}

Some things to note:

- We're creating a hundred buffers a frame. This is inefficent, but we'll cover better ways of doing this later in this tutorial.

- We have to create a new render pass per instance, as we can't modify the uniform buffer while we have one active.

- We use

LoadOp::Loadhere to prevent the render pass from clearing the entire screen after each draw. This means we lose our clear color. This makes the background black on my machine, but it may be filled with garbage data on yours. We can fix this by added another render pass before the loop.

{

encoder.begin_render_pass(&wgpu::RenderPassDescriptor {

color_attachments: &[

wgpu::RenderPassColorAttachmentDescriptor {

attachment: &frame.view,

resolve_target: None,

load_op: wgpu::LoadOp::Clear,

store_op: wgpu::StoreOp::Store,

clear_color: wgpu::Color {

r: 0.1,

g: 0.2,

b: 0.3,

a: 1.0,

},

}

],

depth_stencil_attachment: None,

});

}

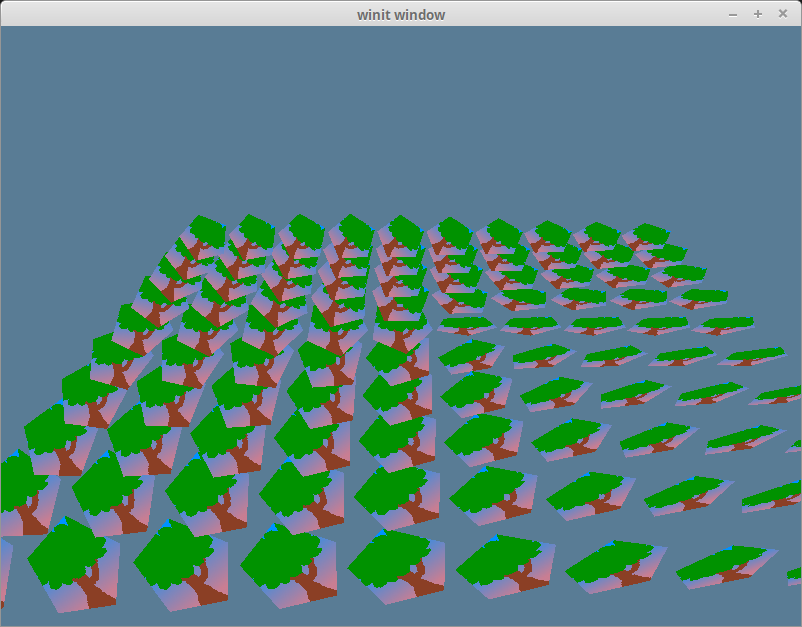

We should get something that looks like this when we're done.

If you haven't guessed already, this way of instancing is not the best. It requires hundreds of render passes, hundereds of staging buffers, and an extra render pass just to get the clear color working again. Cleary there must be a better way.

A better way - uniform arrays

Since GLSL is based on C, it supports arrays. We can leverage this by store all of the instance matrices in the Uniforms struct. We need to make this change on the Rust side, as well as in our shader.

#[repr(C)]

#[derive(Copy, Clone)]

struct Uniforms {

view_proj: cgmath::Matrix4<f32>,

model: [cgmath::Matrix4<f32>; NUM_INSTANCES as usize],

}

#version 450

layout(location=0) in vec3 a_position;

layout(location=1) in vec2 a_tex_coords;

layout(location=0) out vec2 v_tex_coords;

layout(set=1, binding=0)

uniform Uniforms {

mat4 u_view_proj;

mat4 u_model[100];

};

void main() {

v_tex_coords = a_tex_coords;

// gl_InstanceIndex what index we're currently on

gl_Position = u_view_proj * u_model[gl_InstanceIndex] * vec4(a_position, 1.0);

}

Note that we're using an array, not a Vec. Vecs are basically pointers to an array on the heap. Our graphics card doesn't know how follow a pointer to the heap, so our data needs to be stored inline.

Uniforms::new() will change slightly as well.

fn new() -> Self {

Self {

view_proj: cgmath::Matrix4::identity(),

model: [cgmath::Matrix4::identity(); NUM_INSTANCES as usize],

}

}

We need to update our model matrices in State::update() before we create the staging_buffer.

for (i, instance) in self.instances.iter().enumerate() {

self.uniforms.model[i] = instance.to_matrix();

}

Lastly we need to change our render code. Fortunately, it's a lot simpler than the before. In fact we can use the code from last tutorial and just change our draw call.

render_pass.draw_indexed(0..self.num_indices, 0, 0..NUM_INSTANCES);

You'll remember that the 3rd parameter in draw_indexed is the instance range. This controls how many times our object will be drawn. This is where our shader gets the value for gl_InstanceIndex.

Running the program now won't change anything visually from our last example, but the framerate will be better.

This technique has its drawbacks.

- We can't use a

Veclike we've mentioned before - We're limited in the number of instances we can process at a time requiring use to cap it at some abitrary number, or render things in "batches". If we want to increase the size of instances, we have to recompile our code.

Another better way - storage buffers

A storage buffer gives us the flexibility that arrays did not. We don't have to specify it's size in the shader, and we can even use a Vec to create it!

We create a storage buffer in a similar way as any other buffer.

let instance_data = instances.iter().map(Instance::to_matrix).collect::<Vec<_>>();

// we'll need the size for later

let instance_buffer_size = instance_data.len() * std::mem::size_of::<cgmath::Matrix4<f32>>();

let instance_buffer = device

.create_buffer_mapped(instance_data.len(), wgpu::BufferUsage::STORAGE_READ)

.fill_from_slice(&instance_data);

To get this buffer into the shader, we'll need to attach it to a bind group. We'll use uniform_bind_group just to keep things simple.

let uniform_bind_group_layout = device.create_bind_group_layout(&wgpu::BindGroupLayoutDescriptor {

bindings: &[

// ...

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutBinding {

binding: 1,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStage::VERTEX,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::StorageBuffer {

dynamic: false,

readonly: true,

}

}

]

});

let uniform_bind_group = device.create_bind_group(&wgpu::BindGroupDescriptor {

layout: &uniform_bind_group_layout,

bindings: &[

// ...

wgpu::Binding {

binding: 1,

resource: wgpu::BindingResource::Buffer {

buffer: &instance_buffer,

range: 0..instance_buffer_size as wgpu::BufferAddress,

}

}

],

});

Note you'll probably need to shift your instance_buffer creation above the uniform_bind_group creation.

You don't need to change the draw call at all from the previous example, but we'll need to change the vertex shader.

#version 450

layout(location=0) in vec3 a_position;

layout(location=1) in vec2 a_tex_coords;

layout(location=0) out vec2 v_tex_coords;

layout(set=1, binding=0)

uniform Uniforms {

mat4 u_view_proj;

};

layout(set=1, binding=1)

buffer Instances {

mat4 s_models[];

};

void main() {

v_tex_coords = a_tex_coords;

gl_Position = u_view_proj * s_models[gl_InstanceIndex] * vec4(a_position, 1.0);

}

You can see that we got rid of the u_model field from the Uniforms block and create a new Instances located at set=1, binding=1 corresponding with our bind group layout. Another thing to notice is that we use the buffer keyword for the block instead of uniform. The details of the buffer can be found on the OpenGL wiki.

This method is nice because it allows use to store more data overall as storage buffers can theoretically store as much data as the GPU can handle, where uniform buffers are capped. This does mean that storage buffers are slower that uniform buffers as they are stored like other buffers such as textures as and therefore aren't as close in memory, but that usually won't matter much if you're dealing with large amounts of data.

Another benefit to storage buffers is that they can be written to by the shader, unlike uniform buffers. If we want to mutate a large amount of data with a compute shader, we'd use a writeable storage buffer for our output (and potentially input as well).

Another better way - instance buffers

When we created the VertexBufferDescriptor for our model, it required a step_mode field. We used InputStepMode::Vertex, this time we'll create a VertexBufferDescriptor for our instance_buffer.

We'll take the code from the previous example and then create a trait called VBDesc, and implement it for Vertex (replacing the old impl), and a newly created InstanceRaw class. Note: we could just impl VBDesc for cgmath::Matrix4<f32> instead, but instances could have more data in the future, so it's better to create a new struct.

Here's our new trait.

trait VBDesc {

fn desc<'a>() -> wgpu::VertexBufferDescriptor<'a>;

}

To change Vertex to use this, we just have to swap impl Vertex, for impl VBDesc for Vertex.

Now we create InstanceRaw. It's pretty simple.

#[repr(C)]

#[derive(Debug, Copy, Clone)]

struct InstanceRaw {

model: cgmath::Matrix4<f32>,

}

We'll also want to change Instance::to_matrix() to Instance::to_raw().

impl Instance {

fn to_raw(&self) -> InstanceRaw {

let model = cgmath::Matrix4::from_translation(self.position)

* cgmath::Matrix4::from(self.rotation)

InstanceRaw { model }

}

}

Make sure to change any references to to_matrix to to_raw as well. We'll also want to change our BufferUsage to VERTEX.

let instance_data = instances.iter().map(Instance::to_raw).collect::<Vec<_>>();

let instance_buffer = device

.create_buffer_mapped(instance_data.len(), wgpu::BufferUsage::VERTEX)

.fill_from_slice(&instance_data);

With that done we can implement VBDesc for InstanceRaw.

const FLOAT_SIZE: wgpu::BufferAddress = std::mem::size_of::<f32>() as wgpu::BufferAddress;

impl VBDesc for InstanceRaw {

fn desc<'a>() -> wgpu::VertexBufferDescriptor<'a> {

wgpu::VertexBufferDescriptor {

stride: std::mem::size_of::<InstanceRaw>() as wgpu::BufferAddress,

step_mode: wgpu::InputStepMode::Instance, // 1.

attributes: &[

wgpu::VertexAttributeDescriptor {

offset: 0,

format: wgpu::VertexFormat::Float4, // 2.

shader_location: 2, // 3.

},

wgpu::VertexAttributeDescriptor {

offset: FLOAT_SIZE * 4,

format: wgpu::VertexFormat::Float4,

shader_location: 3,

},

wgpu::VertexAttributeDescriptor {

offset: FLOAT_SIZE * 4 * 2,

format: wgpu::VertexFormat::Float4,

shader_location: 4,

},

wgpu::VertexAttributeDescriptor {

offset: FLOAT_SIZE * 4 * 3,

format: wgpu::VertexFormat::Float4,

shader_location: 5,

},

]

}

}

}

Let's unpack this a bit.

- This line makes what would be a vertex buffer into and index buffer. If we didn't specify this, the shader would loop through the elements in this list for every vertex.

- Vertex attributes have a limited size:

Float4or the equivalent. This means that our instance buffer will take up multiple attribute slots. 4 in our case. - Since we're using 2 slots for our

Vertexstruct, we need to start theshader_locationat 2.

Now we need to add our a VertexBufferDescriptor to our render_pipeline.

let render_pipeline = device.create_render_pipeline(&wgpu::RenderPipelineDescriptor {

// ...

vertex_buffers: &[

Vertex::desc(), InstanceRaw::desc(),

],

// ...

});

You'll probably want to remove the BindGroupLayoutBinding and Binding from uniform_bind_group_layout and uniform_bind_group respectively, as we won't be accessing our buffer from there.

This last thing we'll need to do from Rust is use our instance_buffer in the render() method.

render_pass.set_vertex_buffers(0, &[(&self.vertex_buffer, 0), (&self.instance_buffer, 0)]);

Now we get to the shader. We don't have to change much, we just make our shader reference our instance_buffer through the attributes rather than a uniform/buffer block.

#version 450

layout(location=0) in vec3 a_position;

layout(location=1) in vec2 a_tex_coords;

layout(location=2) in mat4 a_model; // NEW!

layout(location=0) out vec2 v_tex_coords;

layout(set=1, binding=0)

uniform Uniforms {

mat4 u_view_proj;

};

void main() {

v_tex_coords = a_tex_coords;

gl_Position = u_view_proj * a_model * vec4(a_position, 1.0); // UPDATED!

}

That's all you need to get an instance buffer working! There's a bit of overhead to get things working, and there are a few quirks, but it gets the job.

A different way - textures

This seems like a really backwards way to do instancing. Storing non image data in a texture seems really bizarre even though it's a perfectly valid thing to do. After all, a texture is just an array of bytes, and that could theoretically be anything. In our case, we're going to cram our matrix data into that array of bytes.

If you're following along, it'd be best to start from the storage buffer example. We're going to modify it to take our instance_buffer, and copy it into a 1D instance_texture. First we need to create the texture.

let instance_extent = wgpu::Extent3d {

width: instance_data.len() as u32 * 4,

height: 1,

depth: 1,

};

let instance_texture = device.create_texture(&wgpu::TextureDescriptor {

size: instance_extent,

array_layer_count: 1,

mip_level_count: 1,

sample_count: 1,

dimension: wgpu::TextureDimension::D1,

format: wgpu::TextureFormat::Rgba32Float,

usage: wgpu::TextureUsage::SAMPLED | wgpu::TextureUsage::COPY_DST,

});

All of this is fairly normal texture creation stuff, save two things:

- We specify the height of the texture as 1. While you could theoretically use a height greater than 1, keeping the texture 1D simplifies things a bit. This also means that we need to use

TextureDimension::D1for ourdimension. - We're using

TextureFormat::Rgba32Floatfor the texture format. Since our matrices are 32bit floats, this makes sense. We could use lower memory formats such asRgba16Float, or evenRgba8UnormSrgb, but we loose precision when we do that. We might not need that precision for basic rendering, but applications that need to model reality definetly do.

With that said, let's create our a texture view and sampler for our instance_texture.

let instance_texture_view = instance_texture.create_default_view();

let instance_sampler = device.create_sampler(&wgpu::SamplerDescriptor {

address_mode_u: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

address_mode_v: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

address_mode_w: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

mag_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Nearest,

min_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Nearest,

minmap_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Nearest,

lod_min_clamp: -100.0,

lod_max_clamp: 100.0,

compare_function: wgpu::CompareFunction::Always,

});

Then we need to copy the instance_buffer to our instance_texture. You may need to move the queue.submit(&[encoder.finish()]); line to use appease the borrow checker.

encoder.copy_buffer_to_texture(

wgpu::BufferCopyView {

buffer: &instance_buffer,

offset: 0,

row_pitch: std::mem::size_of::<f32>() as u32 * 4,

image_height: instance_data.len() * 4,

},

wgpu::TextureCopyView {

texture: &instance_texture,

mip_level: 0,

array_layer: 0,

origin: wgpu::Origin3d::ZERO,

},

instance_extent,

);

Now we need to add our texture and sampler to a bind group. Let with the storage buffer example, we'll use uniform_bind_group and its corresponding layout.

let uniform_bind_group_layout = device.create_bind_group_layout(&wgpu::BindGroupLayoutDescriptor {

bindings: &[

// ...

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutBinding {

binding: 1,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStage::VERTEX,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::SampledTexture {

multisampled: false,

dimension: wgpu::TextureViewDimension::D1,

}

},

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutBinding {

binding: 2,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStage::VERTEX,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::Sampler,

},

]

});

let uniform_bind_group = device.create_bind_group(&wgpu::BindGroupDescriptor {

layout: &uniform_bind_group_layout,

bindings: &[

// ...

wgpu::Binding {

binding: 1,

resource: wgpu::BindingResource::TextureView(&instance_texture_view),

},

wgpu::Binding {

binding: 2,

resource: wgpu::BindingResource::Sampler(&instance_sampler),

},

],

});

With all that done we can now move onto the vertex shader. Let's start with the new uniforms. Don't forget to delete the old buffer block.

// we use a texture1D instead of texture2d because our texture is 1D

layout(set = 1, binding = 1) uniform texture1D t_model;

layout(set = 1, binding = 2) uniform sampler s_model;

The next part is a little more intensive, as there's now built in way to process our texture data as matrix data. We'll have to write a function to do that.

mat4 get_matrix(int index) {

return mat4(

texelFetch(sampler1D(t_model, s_model), index * 4, 0),

texelFetch(sampler1D(t_model, s_model), index * 4 + 1, 0),

texelFetch(sampler1D(t_model, s_model), index * 4 + 2, 0),

texelFetch(sampler1D(t_model, s_model), index * 4 + 3, 0)

);

}

This function takes in the index of the instance of the model we are rendering, and pulls our 4 pixels from the image corresponding to to 4 sets of floats that make up that instance's matrix. It then packs them into a mat4 and returns that.

Now we need to change our main() function to use get_matrix().

void main() {

v_tex_coords = a_tex_coords;

mat4 transform = get_matrix(gl_InstanceIndex);

gl_Position = u_view_proj * transform * vec4(a_position, 1.0);

}

That's a lot more work than the other method's, but it's still good to know that you can use textures store things other then color. This technique does come in handy when other solutions are not available, or not as performant. It's good to be aware of the possibilities!

For fun, here's what our matrix data looks like when converted into a texture (scaled up 10 times)!

Recap

| Technique | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Naive Approach |

|

|

| Uniform Buffer |

|

|

| Storage Buffer |

|

|

| Instance Buffer |

|

|

| Textures |

|

|

About the depth issues...

You may have noticed that some of the back pentagons are rendering in front of the ones in the front. This is a draw order issue. We could solve this by sorting the instances from back to front, that would only work from certain camera angles. A more flexible approach would be to use a depth buffer. We'll talk about those next time.

Challenge

Modify the position and/or rotation of the instances every frame.