| .. | ||

| cleared-window.png | ||

| no-clear.png | ||

| README.md | ||

The Surface

First, some housekeeping: State

For convenience, we're going to pack all the fields into a struct and create some methods for it.

// lib.rs

use winit::window::Window;

struct State<'a> {

surface: wgpu::Surface<'a>,

device: wgpu::Device,

queue: wgpu::Queue,

config: wgpu::SurfaceConfiguration,

size: winit::dpi::PhysicalSize<u32>,

// The window must be declared after the surface so

// it gets dropped after it as the surface contains

// unsafe references to the window's resources.

window: &'a Window,

}

impl<'a> State<'a> {

// Creating some of the wgpu types requires async code

async fn new(window: &'a Window) -> State<'a> {

todo!()

}

pub fn window(&self) -> &Window {

&self.window

}

fn resize(&mut self, new_size: winit::dpi::PhysicalSize<u32>) {

todo!()

}

fn input(&mut self, event: &WindowEvent) -> bool {

todo!()

}

fn update(&mut self) {

todo!()

}

fn render(&mut self) -> Result<(), wgpu::SurfaceError> {

todo!()

}

}

I'm glossing over States fields, but they'll make more sense as I explain the code behind these methods.

State::new()

The code for this is pretty straightforward, but let's break it down a bit.

impl<'a> State<'a> {

// ...

async fn new(window: &'a Window) -> State<'a> {

let size = window.inner_size();

// The instance is a handle to our GPU

// Backends::all => Vulkan + Metal + DX12 + Browser WebGPU

let instance = wgpu::Instance::new(wgpu::InstanceDescriptor {

#[cfg(not(target_arch="wasm32"))]

backends: wgpu::Backends::PRIMARY,

#[cfg(target_arch="wasm32")]

backends: wgpu::Backends::GL,

..Default::default()

});

// # Safety

//

// The surface needs to live as long as the window that created it.

// State owns the window, so this should be safe.

let surface = unsafe { instance.create_surface(&window) }.unwrap();

let adapter = instance.request_adapter(

&wgpu::RequestAdapterOptions {

power_preference: wgpu::PowerPreference::default(),

compatible_surface: Some(&surface),

force_fallback_adapter: false,

},

).await.unwrap();

}

Instance and Adapter

The instance is the first thing you create when using wgpu. Its main purpose

is to create Adapters and Surfaces.

The adapter is a handle for our actual graphics card. You can use this to get information about the graphics card, such as its name and what backend the adapter uses. We use this to create our Device and Queue later. Let's discuss the fields of RequestAdapterOptions.

power_preferencehas two variants:LowPowerandHighPerformance.LowPowerwill pick an adapter that favors battery life, such as an integrated GPU.HighPerformancewill pick an adapter for more power-hungry yet more performant GPU's, such as a dedicated graphics card. WGPU will favorLowPowerif there is no adapter for theHighPerformanceoption.- The

compatible_surfacefield tells wgpu to find an adapter that can present to the supplied surface. - The

force_fallback_adapterforces wgpu to pick an adapter that will work on all hardware. This usually means that the rendering backend will use a "software" system instead of hardware such as a GPU.

The options I've passed to request_adapter aren't guaranteed to work for all devices, but will work for most of them. If wgpu can't find an adapter with the required permissions, request_adapter will return None. If you want to get all adapters for a particular backend, you can use enumerate_adapters. This will give you an iterator that you can loop over to check if one of the adapters works for your needs.

let adapter = instance

.enumerate_adapters(wgpu::Backends::all())

.filter(|adapter| {

// Check if this adapter supports our surface

adapter.is_surface_supported(&surface)

})

.next()

.unwrap()

One thing to note is that enumerate_adapters isn't available on WASM, so you have to use request_adapter.

Another thing to note is that Adapters are locked to a specific backend. If you are on Windows and have two graphics cards, you'll have at least four adapters available to use: 2 Vulkan and 2 DirectX.

For more fields you can use to refine your search, check out the docs.

The Surface

The surface is the part of the window that we draw to. We need it to draw directly to the screen. Our window needs to implement raw-window-handle's HasRawWindowHandle trait to create a surface. Fortunately, winit's Window fits the bill. We also need it to request our adapter.

Device and Queue

Let's use the adapter to create the device and queue.

let (device, queue) = adapter.request_device(

&wgpu::DeviceDescriptor {

required_features: wgpu::Features::empty(),

// WebGL doesn't support all of wgpu's features, so if

// we're building for the web, we'll have to disable some.

required_limits: if cfg!(target_arch = "wasm32") {

wgpu::Limits::downlevel_webgl2_defaults()

} else {

wgpu::Limits::default()

},

label: None,

},

None, // Trace path

).await.unwrap();

The features field on DeviceDescriptor allows us to specify what extra features we want. For this simple example, I've decided not to use any extra features.

The graphics card you haverequired_limits the features you can use. If you want to use certain features, you may need to limit what devices you support or provide workarounds.

You can get a list of features supported by your device using adapter.features() or device.features().

You can view a full list of features here.

The limits field describes the limit of certain types of resources that we can create. We'll use the defaults for this tutorial so we can support most devices. You can view a list ofrequired_limits here.

let surface_caps = surface.get_capabilities(&adapter);

// Shader code in this tutorial assumes an sRGB surface texture. Using a different

// one will result in all the colors coming out darker. If you want to support non

// sRGB surfaces, you'll need to account for that when drawing to the frame.

let surface_format = surface_caps.formats.iter()

.copied()

.filter(|f| f.is_srgb())

.next()

.unwrap_or(surface_caps.formats[0]);

let config = wgpu::SurfaceConfiguration {

usage: wgpu::TextureUsages::RENDER_ATTACHMENT,

format: surface_format,

width: size.width,

height: size.height,

present_mode: surface_caps.present_modes[0],

alpha_mode: surface_caps.alpha_modes[0],

view_formats: vec![],

desired_maximum_frame_latency: 2,

};

Here we are defining a config for our surface. This will define how the surface creates its underlying SurfaceTextures. We will talk about SurfaceTexture when we get to the render function. For now, let's talk about the config's fields.

The usage field describes how SurfaceTextures will be used. RENDER_ATTACHMENT specifies that the textures will be used to write to the screen (we'll talk about more TextureUsagess later).

The format defines how SurfaceTextures will be stored on the GPU. We can get a supported format from the SurfaceCapabilities.

width and height are the width and the height in pixels of a SurfaceTexture. This should usually be the width and the height of the window.

present_mode uses wgpu::PresentMode enum, which determines how to sync the surface with the display. For the sake of simplicity, we select the first available option. If you do not want runtime selection, PresentMode::Fifo will cap the display rate at the display's framerate. This is essentially VSync. This mode is guaranteed to be supported on all platforms. There are other options, and you can see all of them in the docs

If you want to let your users pick what PresentMode they use, you can use SurfaceCapabilities::present_modes to get a list of all the PresentModes the surface supports:

let modes = &surface_caps.present_modes;

Regardless, PresentMode::Fifo will always be supported, and PresentMode::AutoVsync and PresentMode::AutoNoVsync have fallback support and therefore will work on all platforms.

alpha_mode is honestly not something I'm familiar with. I believe it has something to do with transparent windows, but feel free to open a pull request. For now, we'll just use the first AlphaMode in the list given by surface_caps.

view_formats is a list of TextureFormats that you can use when creating TextureViews (we'll cover those briefly later in this tutorial as well as more in depth in the texture tutorial). As of writing, this means that if your surface is sRGB color space, you can create a texture view that uses a linear color space.

Now that we've configured our surface properly, we can add these new fields at the end of the method.

async fn new(window: &'a Window) -> State<'a> {

// ...

Self {

window,

surface,

device,

queue,

config,

size,

}

}

Since our State::new() method is async, we need to change run() to be async as well so that we can await it.

Our window has beened moved to the State instance, we will need to update our event_loop to reflect this.

#[cfg_attr(target_arch = "wasm32", wasm_bindgen(start))]

pub async fn run() {

// Window setup...

let mut state = State::new(&window).await;

event_loop.run(move |event, control_flow| {

match event {

Event::WindowEvent {

ref event,

window_id,

} if window_id == state.window().id() => match event {

WindowEvent::CloseRequested

| WindowEvent::KeyboardInput {

input:

KeyboardInput {

state: ElementState::Pressed,

virtual_keycode: Some(VirtualKeyCode::Escape),

..

},

..

} => *control_flow = ControlFlow::Exit,

_ => {}

},

_ => {}

}

});

}

Now that run() is async, main() will need some way to await the future. We could use a crate like tokio, or async-std, but I'm going to go with the much more lightweight pollster. Add the following to your Cargo.toml:

[dependencies]

# other deps...

pollster = "0.3"

We then use the block_on function provided by pollster to await our future:

fn main() {

pollster::block_on(run());

}

Don't use block_on inside of an async function if you plan to support WASM. Futures have to be run using the browser's executor. If you try to bring your own, your code will crash when you encounter a future that doesn't execute immediately.

If we try to build WASM now, it will fail because wasm-bindgen doesn't support using async functions as start methods. You could switch to calling run manually in javascript, but for simplicity, we'll add the wasm-bindgen-futures crate to our WASM dependencies as that doesn't require us to change any code. Your dependencies should look something like this:

[dependencies]

cfg-if = "1"

winit = { version = "0.29", features = ["rwh_05"] }

env_logger = "0.10"

log = "0.4"

wgpu = "0.19"

pollster = "0.3"

[target.'cfg(target_arch = "wasm32")'.dependencies]

console_error_panic_hook = "0.1.6"

console_log = "1.0"

wgpu = { version = "0.19", features = ["webgl"]}

wasm-bindgen = "0.2"

wasm-bindgen-futures = "0.4"

web-sys = { version = "0.3", features = [

"Document",

"Window",

"Element",

]}

resize()

If we want to support resizing in our application, we're going to need to reconfigure the surface every time the window's size changes. That's the reason we stored the physical size and the config used to configure the surface. With all of these, the resize method is very simple.

// impl State

pub fn resize(&mut self, new_size: winit::dpi::PhysicalSize<u32>) {

if new_size.width > 0 && new_size.height > 0 {

self.size = new_size;

self.config.width = new_size.width;

self.config.height = new_size.height;

self.surface.configure(&self.device, &self.config);

}

}

There's nothing different here from the initial surface configuration, so I won't get into it.

We call this method run() in the event loop for the following events.

match event {

// ...

} if window_id == state.window().id() => if !state.input(event) {

match event {

// ...

WindowEvent::Resized(physical_size) => {

state.resize(*physical_size);

}

WindowEvent::ScaleFactorChanged { new_inner_size, .. } => {

// new_inner_size is &&mut so we have to dereference it twice

state.resize(**new_inner_size);

}

// ...

}

}

}

input()

input() returns a bool to indicate whether an event has been fully processed. If the method returns true, the main loop won't process the event any further.

We're just going to return false for now because we don't have any events we want to capture.

// impl State

fn input(&mut self, event: &WindowEvent) -> bool {

false

}

We need to do a little more work in the event loop. We want State to have priority over run(). Doing that (and previous changes) should make your loop look like this.

// run()

event_loop.run(move |event, _, control_flow| {

match event {

Event::WindowEvent {

ref event,

window_id,

} if window_id == state.window().id() => if !state.input(event) { // UPDATED!

match event {

WindowEvent::CloseRequested

| WindowEvent::KeyboardInput {

input:

KeyboardInput {

state: ElementState::Pressed,

virtual_keycode: Some(VirtualKeyCode::Escape),

..

},

..

} => *control_flow = ControlFlow::Exit,

WindowEvent::Resized(physical_size) => {

state.resize(*physical_size);

}

WindowEvent::ScaleFactorChanged { new_inner_size, .. } => {

state.resize(**new_inner_size);

}

_ => {}

}

}

_ => {}

}

});

update()

We don't have anything to update yet, so leave the method empty.

fn update(&mut self) {

// remove `todo!()`

}

We'll add some code here later on to move around objects.

render()

Here's where the magic happens. First, we need to get a frame to render to.

// impl State

fn render(&mut self) -> Result<(), wgpu::SurfaceError> {

let output = self.surface.get_current_texture()?;

The get_current_texture function will wait for the surface to provide a new SurfaceTexture that we will render to. We'll store this in output for later.

let view = output.texture.create_view(&wgpu::TextureViewDescriptor::default());

This line creates a TextureView with default settings. We need to do this because we want to control how the render code interacts with the texture.

We also need to create a CommandEncoder to create the actual commands to send to the GPU. Most modern graphics frameworks expect commands to be stored in a command buffer before being sent to the GPU. The encoder builds a command buffer that we can then send to the GPU.

let mut encoder = self.device.create_command_encoder(&wgpu::CommandEncoderDescriptor {

label: Some("Render Encoder"),

});

Now we can get to clearing the screen (a long time coming). We need to use the encoder to create a RenderPass. The RenderPass has all the methods for the actual drawing. The code for creating a RenderPass is a bit nested, so I'll copy it all here before talking about its pieces.

{

let _render_pass = encoder.begin_render_pass(&wgpu::RenderPassDescriptor {

label: Some("Render Pass"),

color_attachments: &[Some(wgpu::RenderPassColorAttachment {

view: &view,

resolve_target: None,

ops: wgpu::Operations {

load: wgpu::LoadOp::Clear(wgpu::Color {

r: 0.1,

g: 0.2,

b: 0.3,

a: 1.0,

}),

store: wgpu::StoreOp::Store,

},

})],

depth_stencil_attachment: None,

occlusion_query_set: None,

timestamp_writes: None,

});

}

// submit will accept anything that implements IntoIter

self.queue.submit(std::iter::once(encoder.finish()));

output.present();

Ok(())

}

First things first, let's talk about the extra block ({}) around encoder.begin_render_pass(...). begin_render_pass() borrows encoder mutably (aka &mut self). We can't call encoder.finish() until we release that mutable borrow. The block tells Rust to drop any variables within it when the code leaves that scope, thus releasing the mutable borrow on encoder and allowing us to finish() it. If you don't like the {}, you can also use drop(render_pass) to achieve the same effect.

The last lines of the code tell wgpu to finish the command buffer and submit it to the GPU's render queue.

We need to update the event loop again to call this method. We'll also call update() before it, too.

// run()

event_loop.run(move |event, _, control_flow| {

match event {

// ...

Event::RedrawRequested(window_id) if window_id == state.window().id() => {

state.update();

match state.render() {

Ok(_) => {}

// Reconfigure the surface if lost

Err(wgpu::SurfaceError::Lost) => state.resize(state.size),

// The system is out of memory, we should probably quit

Err(wgpu::SurfaceError::OutOfMemory) => *control_flow = ControlFlow::Exit,

// All other errors (Outdated, Timeout) should be resolved by the next frame

Err(e) => eprintln!("{:?}", e),

}

}

Event::MainEventsCleared => {

// RedrawRequested will only trigger once unless we manually

// request it.

state.window().request_redraw();

}

// ...

}

});

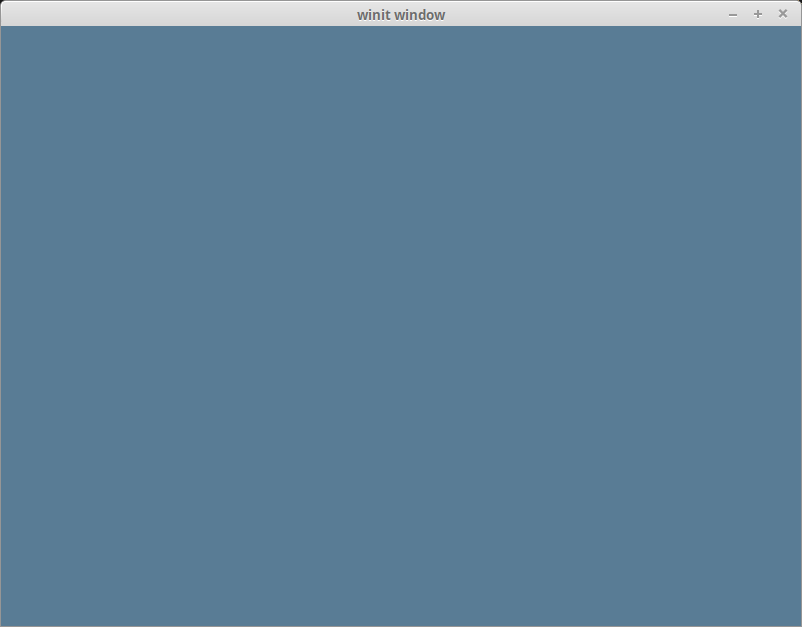

With all that, you should be getting something that looks like this.

Wait, what's going on with RenderPassDescriptor?

Some of you may be able to tell what's going on just by looking at it, but I'd be remiss if I didn't go over it. Let's take a look at the code again.

&wgpu::RenderPassDescriptor {

label: Some("Render Pass"),

color_attachments: &[

// ...

],

depth_stencil_attachment: None,

}

A RenderPassDescriptor only has three fields: label, color_attachments and depth_stencil_attachment. The color_attachments describe where we are going to draw our color to. We use the TextureView we created earlier to make sure that we render to the screen.

The color_attachments field is a "sparse" array. This allows you to use a pipeline that expects multiple render targets and only supplies the ones you care about.

We'll use depth_stencil_attachment later, but we'll set it to None for now.

Some(wgpu::RenderPassColorAttachment {

view: &view,

resolve_target: None,

ops: wgpu::Operations {

load: wgpu::LoadOp::Clear(wgpu::Color {

r: 0.1,

g: 0.2,

b: 0.3,

a: 1.0,

}),

store: wgpu::StoreOp::Store,

},

})

The RenderPassColorAttachment has the view field, which informs wgpu what texture to save the colors to. In this case, we specify the view that we created using surface.get_current_texture(). This means that any colors we draw to this attachment will get drawn to the screen.

The resolve_target is the texture that will receive the resolved output. This will be the same as view unless multisampling is enabled. We don't need to specify this, so we leave it as None.

The ops field takes a wpgu::Operations object. This tells wgpu what to do with the colors on the screen (specified by view). The load field tells wgpu how to handle colors stored from the previous frame. Currently, we are clearing the screen with a bluish color. The store field tells wgpu whether we want to store the rendered results to the Texture behind our TextureView (in this case, it's the SurfaceTexture). We use StoreOp::Store as we do want to store our render results.

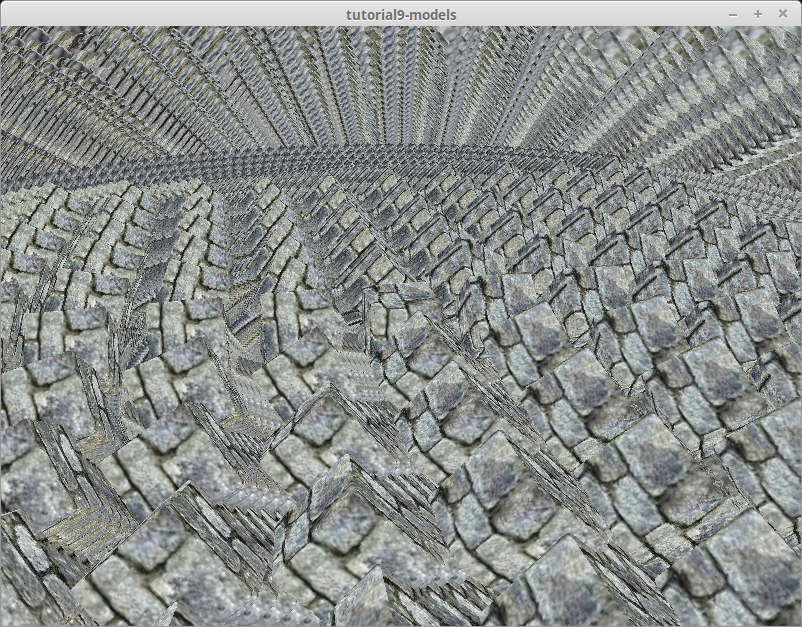

It's not uncommon to not clear the screen if the screen is going to be completely covered up with objects. If your scene doesn't cover the entire screen, however, you can end up with something like this.

Validation Errors?

If wgpu is using Vulkan on your machine, you may run into validation errors if you are running an older version of the Vulkan SDK. You should be using at least version 1.2.182 as older versions can give out some false positives. If errors persist, you may have encountered a bug in wgpu. You can post an issue at https://github.com/gfx-rs/wgpu

Challenge

Modify the input() method to capture mouse events, and update the clear color using that. Hint: you'll probably need to use WindowEvent::CursorMoved.