| .. | ||

| address_mode.png | ||

| address_mode.xcf | ||

| happy-tree-uv-coords.png | ||

| happy-tree-uv-coords.xcf | ||

| happy-tree.png | ||

| happy-tree.xcf | ||

| README.md | ||

| rightside-up.png | ||

| upside-down.png | ||

Textures and bind groups

Up to this point we have been drawing super simple shapes. While we can make a game with just triangles, but trying to draw highly detailed objects would massively limit what devices could even run our game. We can get around this problem with textures. Textures are images overlayed over a triangle mesh to make the mesh seem more detailed. There are multiple types of textures such as normal maps, bump maps, specular maps, and diffuse maps. We're going to talk about diffuse maps, or in laymens terms, the color texture.

Loading an image from a file

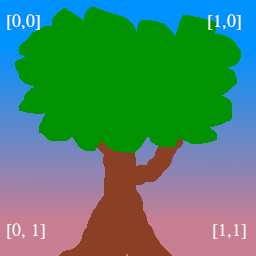

If we want to map an image to our mesh, we first need an image. Let's use this happy little tree.

We'll use the image crate to load our tree. In State's new() method add the following just after creating the swap_chain:

let diffuse_bytes = include_bytes!("happy-tree.png");

let diffuse_image = image::load_from_memory(diffuse_bytes).unwrap();

let diffuse_rgba = diffuse_image.as_rgba8().unwrap();

use image::GenericImageView;

let dimensions = diffuse_image.dimensions();

Here we just grab the bytes from our image file, and load them into an image, which we then convert into a Vec of rgba bytes. We also save the image's dimensions for when we create the actual Texture. Speaking of creating the actual Texture.

let size = wgpu::Extent3d {

width: dimensions.0,

height: dimensions.1,

depth: 1,

};

let diffuse_texture = device.create_texture(

&wgpu::TextureDescriptor {

// All textures are stored as 3d, we represent our 2d texture

// by setting depth to 1.

size: wgpu::Extent3d {

width: dimensions.0,

height: dimensions.1,

depth: 1,

},

mip_level_count: 1, // We'll talk about this a little later

sample_count: 1,

dimension: wgpu::TextureDimension::D2,

format: wgpu::TextureFormat::Rgba8UnormSrgb,

// SAMPLED tells wgpu that we want to use this texture in shaders

// COPY_DST means that we want to copy data to this texture

usage: wgpu::TextureUsage::SAMPLED | wgpu::TextureUsage::COPY_DST,

label: Some("diffuse_texture"),

}

);

Getting data into a Texture

The Texture struct has no methods to interact with the data directly. However we can use a method on the queue called write_texture. Let's take a look at how to use it.

queue.write_texture(

// Tells wgpu where to copy the pixel data

wgpu::TextureCopyView {

texture: &diffuse_texture,

mip_level: 0,

origin: wgpu::Origin3d::ZERO,

},

// The actual pixel data

diffuse_rgba,

// The layout of the texture

wgpu::TextureDataLayout {

offset: 0,

bytes_per_row: 4 * dimensions.0,

rows_per_image: dimensions.1,

},

size,

);

The old way of writing data to a texture was to copy the pixel data to a buffer, and then copy it to the texture. Using write_texture is a bit more efficient as it uses one less buffer. I'll leave it here though in case you need it.

let buffer = device.create_buffer_init(

&wgpu::util::BufferInitDescriptor {

label: Some("Temp Buffer"),

&diffuse_rgba,

wgpu::BufferUsage::COPY_SRC,

}

);

let mut encoder = device.create_command_encoder(&wgpu::CommandEncoderDescriptor {

label: Some("texture_buffer_copy_encoder"),

});

encoder.copy_buffer_to_texture(

wgpu::BufferCopyView {

buffer: &buffer,

offset: 0,

bytes_per_row: 4 * dimensions.0,

rows_per_image: dimensions.1,

},

wgpu::TextureCopyView {

texture: &diffuse_texture,

mip_level: 0,

array_layer: 0,

origin: wgpu::Origin3d::ZERO,

},

size,

);

queue.submit(std::iter::once(encoder.finish()));

They bytes_per_row field needs some consideration. This value needs to be a multiple of 256. Check out the gif tutorial for more details.

TextureViews and Samplers

Now that our texture has data in it, we need a way to use it. This is where a TextureView and a Sampler come in. A TextureView offers us a view into our texture. A Sampler controls how the Texture is sampled. Sampling works similar to the eyedropper tool in Gimp/Photoshop. Our program supplies a coordinate on the texture (known as a texture coordinate), and the sampler then returns a color back based on it's internal parameters.

Let's define our diffuse_texture_view and diffuse_sampler now.

// We don't need to configure the texture view much, so let's

// let wgpu define it.

let diffuse_texture_view = diffuse_texture.create_view(&wgpu::TextureViewDescriptor::default());

let diffuse_sampler = device.create_sampler(&wgpu::SamplerDescriptor {

address_mode_u: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

address_mode_v: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

address_mode_w: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

mag_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Linear,

min_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Nearest,

mipmap_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Nearest,

..Default::default()

});

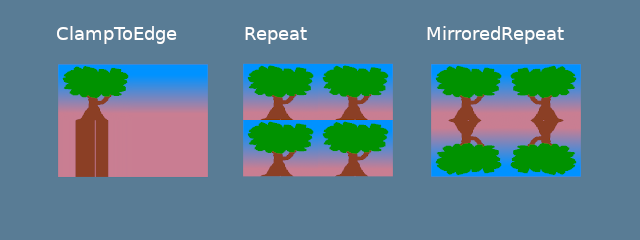

The address_mode_* parameter's determine what to do if the sampler get's a texture coordinate that's outside of the texture. There's a few that we can use.

ClampToEdge: Any texture coordinates outside the texture will return the color of the nearest pixel on the edges of the texture.Repeat: The texture will repeat as texture coordinates exceed the textures dimensions.MirrorRepeat: Similar toRepeat, but the image will flip when going over boundaries.

The mag_filter and min_filter options describe what to do when a fragment covers multiple pixels, or there are multiple fragments for one pixel respectively. This often comes into play when viewing a surface from up close, or far away. There are 2 options:

Linear: This option will attempt to blend the in-between fragments so that they seem to flow together.Nearest: In-between fragments will use the color of the nearest pixel. This creates an image that's crisper from far away, but pixelated when view from close up. This can be desirable however if your textures are designed to be pixelated such is in pixel art games, or voxel games like Minecraft.

Mipmaps are a complex topic, and will require their own section. Suffice to say mipmap_filter functions similar to (mag/min)_filter as it tells the sampler how to blend between mipmaps.

I'm using some defaults for the other fields. If you want to see what they are check the docs.

All these different resources are nice and all, but they doesn't do us much good if we can't plug them in anywhere. This is where BindGroups and PipelineLayouts come in.

The BindGroup

A BindGroup describes a set of resources and how they can be accessed by a shader. We create a BindGroup using a BindGroupLayout. Let's make one of those first.

let texture_bind_group_layout = device.create_bind_group_layout(

&wgpu::BindGroupLayoutDescriptor {

entries: &[

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutEntry {

binding: 0,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStage::FRAGMENT,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::SampledTexture {

multisampled: false,

dimension: wgpu::TextureViewDimension::D2,

component_type: wgpu::TextureComponentType::Uint,

},

count: None,

},

wgpu::BindGroupLayoutEntry {

binding: 1,

visibility: wgpu::ShaderStage::FRAGMENT,

ty: wgpu::BindingType::Sampler {

comparison: false,

},

count: None,

},

],

label: Some("texture_bind_group_layout"),

}

);

Our texture_bind_group_layout has two entries: one for a sampled texture at binding 0, and one for a sampler at binding 1. Both of these bindings are visible only to the fragment shader as specified by FRAGMENT. The possible values are any bit combination of NONE, VERTEX, FRAGMENT, or COMPUTE. Most of the time we'll only use FRAGMENT for textures and samplers, but it's good to know what's available.

With texture_bind_group_layout, we can now create our BindGroup.

let diffuse_bind_group = device.create_bind_group(

&wgpu::BindGroupDescriptor {

layout: &texture_bind_group_layout,

entries: &[

wgpu::BindGroupEntry {

binding: 0,

resource: wgpu::BindingResource::TextureView(&diffuse_texture.view),

},

wgpu::BindGroupEntry {

binding: 1,

resource: wgpu::BindingResource::Sampler(&diffuse_texture.sampler),

}

],

label: Some("diffuse_bind_group"),

}

);

Looking at this you might get a bit of déjà vu. That's because a BindGroup is a more specific declaration of the BindGroupLayout. The reason why these are separate is to allow us to swap out BindGroups on the fly, so long as they all share the same BindGroupLayout. For each texture and sampler we create, we need to create a BindGroup.

Now that we have our diffuse_bind_group, let's add our texture information to the State struct.

struct State {

// ...

diffuse_texture: wgpu::Texture,

diffuse_texture_view: wgpu::TextureView,

diffuse_sampler: wgpu::Sampler,

diffuse_bind_group: wgpu::BindGroup,

// ...

}

// ...

impl State {

async fn new() -> Self {

// ...

Self {

surface,

device,

queue,

sc_desc,

swap_chain,

render_pipeline,

vertex_buffer,

index_buffer,

num_indices,

diffuse_texture,

diffuse_texture_view,

diffuse_sampler,

diffuse_bind_group,

size,

}

}

}

We actually use the bind group in the render() function.

// render()

render_pass.set_pipeline(&self.render_pipeline);

render_pass.set_bind_group(0, &self.diffuse_bind_group, &[]); // NEW!

render_pass.set_vertex_buffer(0, &self.vertex_buffer.slice(..));

render_pass.set_index_buffer(&self.index_buffer.slice(..));

render_pass.draw_indexed(0..self.num_indices, 0, 0..1);

The order of these statements is important. The pipeline needs to be set first, then the bind groups, vertex buffers, and index buffer, finally the draw call. If you don't do this, you'll likely get a crash.

PipelineLayout

Remember the PipelineLayout we created back in the pipeline section? This is finally the time when we get to actually use it. The PipelineLayout contains a list of BindGroupLayouts that the pipeline can use. Modify render_pipeline_layout to use our texture_bind_group_layout.

let render_pipeline_layout = device.create_pipeline_layout(

&wgpu::PipelineLayoutDescriptor {

label: Some("Render Pipeline Layout"),

bind_group_layouts: &[&texture_bind_group_layout],

push_constant_ranges: &[],

}

);

A change to the VERTICES

There's a few things we need to change about our Vertex definition. Up to now we've been using a color attribute to dictate the color of our mesh. Now that we're using a texture we want to replace our color with tex_coords, which is only two floats instead of three.

#[repr(C)]

#[derive(Copy, Clone, Debug)]

struct Vertex {

position: [f32; 3],

tex_coords: [f32; 2],

}

We need to reflect these changes in the VertexBufferDescriptor.

impl Vertex {

fn desc<'a>() -> wgpu::VertexBufferDescriptor<'a> {

use std::mem;

wgpu::VertexBufferDescriptor {

stride: mem::size_of::<Vertex>() as wgpu::BufferAddress,

step_mode: wgpu::InputStepMode::Vertex,

attributes: &[

wgpu::VertexAttributeDescriptor {

offset: 0,

shader_location: 0,

format: wgpu::VertexFormat::Float3,

},

wgpu::VertexAttributeDescriptor {

offset: mem::size_of::<[f32; 3]>() as wgpu::BufferAddress,

shader_location: 1,

format: wgpu::VertexFormat::Float2,

},

]

}

}

}

Lastly we need to change VERTICES itself.

const VERTICES: &[Vertex] = &[

Vertex { position: [-0.0868241, 0.49240386, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.4131759, 0.99240386], }, // A

Vertex { position: [-0.49513406, 0.06958647, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.0048659444, 0.56958646], }, // B

Vertex { position: [-0.21918549, -0.44939706, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.28081453, 0.050602943], }, // C

Vertex { position: [0.35966998, -0.3473291, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.85967, 0.15267089], }, // D

Vertex { position: [0.44147372, 0.2347359, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.9414737, 0.7347359], }, // E

];

Shader time

Our shaders will need to change inorder to support textures as well. We'll also need to remove any reference to the color attribute we used to have. Let's start with the vertex shader.

// shader.vert

#version 450

layout(location=0) in vec3 a_position;

// Changed

layout(location=1) in vec2 a_tex_coords;

// Changed

layout(location=0) out vec2 v_tex_coords;

void main() {

// Changed

v_tex_coords = a_tex_coords;

gl_Position = vec4(a_position, 1.0);

}

We need to change the fragment shader to take in v_tex_coords. We also need to add a reference to our texture and sampler.

// shader.frag

#version 450

// Changed

layout(location=0) in vec2 v_tex_coords;

layout(location=0) out vec4 f_color;

// New

layout(set = 0, binding = 0) uniform texture2D t_diffuse;

layout(set = 0, binding = 1) uniform sampler s_diffuse;

void main() {

// Changed

f_color = texture(sampler2D(t_diffuse, s_diffuse), v_tex_coords);

}

You'll notice that t_diffuse and s_diffuse are defined with the uniform keyword, they don't have in nor out, and the layout definition uses set and binding instead of location. This is because t_diffuse and s_diffuse are what we call uniforms. We won't go too deep into what a uniform is, until we talk about uniform buffers in the cameras section. What we need to know, for now, is that set = 0 corresponds to the 1st parameter in set_bind_group(), binding = 0 relates the the binding specified when we create the BindGroupLayout and BindGroup.

The results

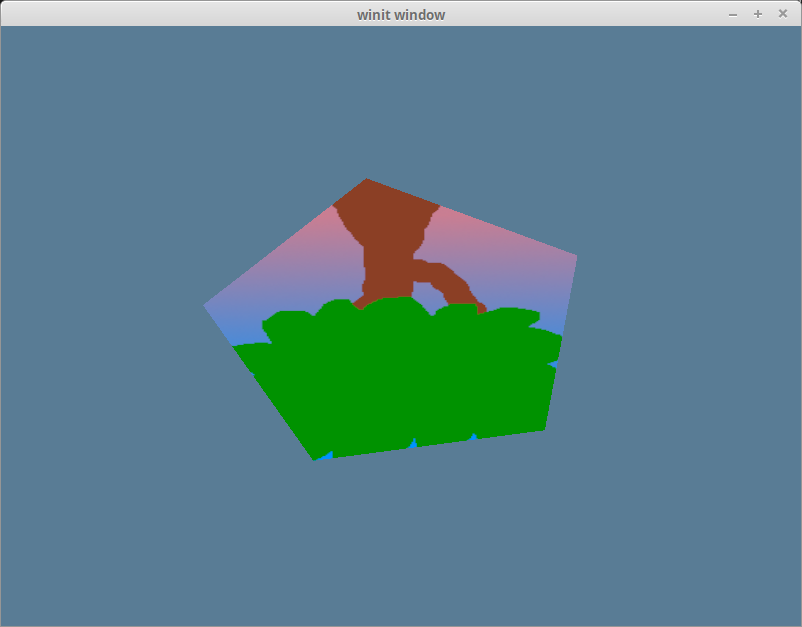

If we run our program now we should get the following result.

That's weird, our tree is upside down! This is because wgpu's world coordinates have the y-axis pointing up, while texture coordinates have the y-axis pointing down. In other words, (0, 0) in texture coordinates coresponds to the top-left of the image, while (1, 1) is the bottom right.

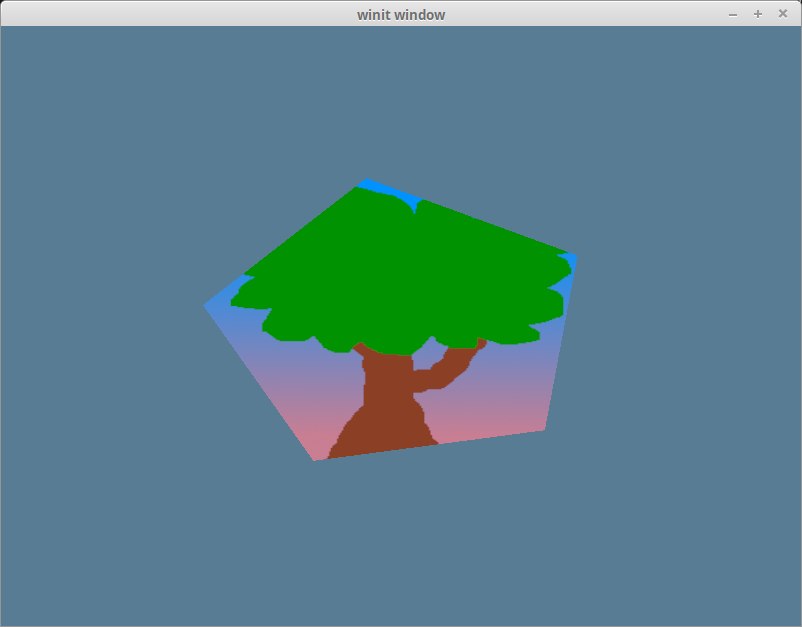

We can get our triangle right-side up by inverting the y coord of each texture coord.

const VERTICES: &[Vertex] = &[

Vertex { position: [-0.0868241, 0.49240386, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.4131759, 1.0 - 0.99240386], }, // A

Vertex { position: [-0.49513406, 0.06958647, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.0048659444, 1.0 - 0.56958646], }, // B

Vertex { position: [-0.21918549, -0.44939706, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.28081453, 1.0 - 0.050602943], }, // C

Vertex { position: [0.35966998, -0.3473291, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.85967, 1.0 - 0.15267089], }, // D

Vertex { position: [0.44147372, 0.2347359, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.9414737, 1.0 - 0.7347359], }, // E

];

Simplifying that gives us.

const VERTICES: &[Vertex] = &[

Vertex { position: [-0.0868241, 0.49240386, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.4131759, 0.00759614], }, // A

Vertex { position: [-0.49513406, 0.06958647, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.0048659444, 0.43041354], }, // B

Vertex { position: [-0.21918549, -0.44939706, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.28081453, 0.949397057], }, // C

Vertex { position: [0.35966998, -0.3473291, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.85967, 0.84732911], }, // D

Vertex { position: [0.44147372, 0.2347359, 0.0], tex_coords: [0.9414737, 0.2652641], }, // E

];

With that in place we now have our tree subscribed right-side up on our hexagon.

Cleaning things up

For convenience sake, let's pull our texture code into its own file called texture.rs.

use image::GenericImageView;

use anyhow::*;

pub struct Texture {

pub texture: wgpu::Texture,

pub view: wgpu::TextureView,

pub sampler: wgpu::Sampler,

}

impl Texture {

pub fn from_bytes(

device: &wgpu::Device,

queue: &wgpu::Queue,

bytes: &[u8],

label: &str

) -> Result<Self> {

let img = image::load_from_memory(bytes)?;

Self::from_image(device, queue, &img, Some(label))

}

pub fn from_image(

device: &wgpu::Device,

queue: &wgpu::Queue,

img: &image::DynamicImage,

label: Option<&str>

) -> Result<Self> {

let rgba = img.as_rgba8().unwrap();

let dimensions = img.dimensions();

let size = wgpu::Extent3d {

width: dimensions.0,

height: dimensions.1,

depth: 1,

};

let texture = device.create_texture(

&wgpu::TextureDescriptor {

label,

size,

mip_level_count: 1,

sample_count: 1,

dimension: wgpu::TextureDimension::D2,

format: wgpu::TextureFormat::Rgba8UnormSrgb,

usage: wgpu::TextureUsage::SAMPLED | wgpu::TextureUsage::COPY_DST,

}

);

queue.write_texture(

wgpu::TextureCopyView {

texture: &texture,

mip_level: 0,

origin: wgpu::Origin3d::ZERO,

},

rgba,

wgpu::TextureDataLayout {

offset: 0,

bytes_per_row: 4 * dimensions.0,

rows_per_image: dimensions.1,

},

size,

);

let view = texture.create_view(&wgpu::TextureViewDescriptor::default());

let sampler = device.create_sampler(

&wgpu::SamplerDescriptor {

address_mode_u: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

address_mode_v: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

address_mode_w: wgpu::AddressMode::ClampToEdge,

mag_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Linear,

min_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Nearest,

mipmap_filter: wgpu::FilterMode::Nearest,

..Default::default()

}

);

Ok(Self { texture, view, sampler })

}

}

- We're using the anyhow crate to simplify error handling.

- We're returning a

CommandBufferwith our texture. This means we could load multiple textures at the same time, and then submit all there command buffers at once.

We need to import texture.rs as a module, so somewhere at the top of main.rs add the following.

mod texture;

Then we need to change State to use the Texture struct.

struct State {

diffuse_texture: texture::Texture,

diffuse_bind_group: wgpu::BindGroup,

}

We're storing the bind group separately so that Texture doesn't need know how the BindGroup is layed out.

The texture creation code in new() gets a lot simpler.

let diffuse_bytes = include_bytes!("happy-tree.png");

let diffuse_texture = texture::Texture::from_bytes(&device, diffuse_bytes, "happy-tree.png").unwrap();

Creating the diffuse_bind_group changes slightly to use the view and sampler fields of our diffuse_texture.

let diffuse_bind_group = device.create_bind_group(

&wgpu::BindGroupDescriptor {

layout: &texture_bind_group_layout,

entries: &[

wgpu::BindGroupEntry {

binding: 0,

resource: wgpu::BindingResource::TextureView(&diffuse_texture.view),

},

wgpu::BindGroupEntry {

binding: 1,

resource: wgpu::BindingResource::Sampler(&diffuse_texture.sampler),

}

],

label: Some("diffuse_bind_group"),

}

);

The code should be working the same as it was before, but now have an easier way to create textures.

Challenge

Create another texture and swap it out when you press the space key.